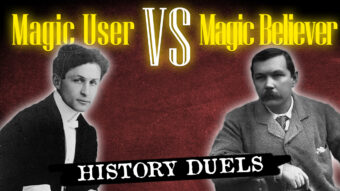

Erik Weiss, better known by his stage name Harry Houdini, was one of the greatest entertainers in history, and among the first modern mega-celebrities. Over a 35-year career spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Houdini thrilled audiences the world over with his headline-grabbing feats of stage magic and death-defying escapology, making entire elephants disappear and wriggling his way out of every kind of restraint imaginable, from handcuffs and shackles to prison cells, straitjackets, milk cans full of water, and locked trunks dropped into rivers and lakes. But despite the sensationalist posters and headlines painting Houdini as a shadowy master of the mystic arts, the man himself was no believer in the supernatural. A consummate professional, Houdini openly acknowledged that his seemingly miraculous feats were the products of illusion, sleight-of-hand, and hard work, and vehemently opposed anyone who claimed otherwise. And both onstage and off the great illusionist waged a passionate crusade against mediums, mystics, and fortune-tellers, whom he saw as mere frauds and charlatans who used the cheap tricks of stage magic to swindle the gullible and the vulnerable. It was a campaign which was to make Houdini many enemies, destroy his friendship with one of the most popular authors of his time, and bring him all the way to the halls of the U.S. Congress.

Erik Weiss, better known by his stage name Harry Houdini, was one of the greatest entertainers in history, and among the first modern mega-celebrities. Over a 35-year career spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Houdini thrilled audiences the world over with his headline-grabbing feats of stage magic and death-defying escapology, making entire elephants disappear and wriggling his way out of every kind of restraint imaginable, from handcuffs and shackles to prison cells, straitjackets, milk cans full of water, and locked trunks dropped into rivers and lakes. But despite the sensationalist posters and headlines painting Houdini as a shadowy master of the mystic arts, the man himself was no believer in the supernatural. A consummate professional, Houdini openly acknowledged that his seemingly miraculous feats were the products of illusion, sleight-of-hand, and hard work, and vehemently opposed anyone who claimed otherwise. And both onstage and off the great illusionist waged a passionate crusade against mediums, mystics, and fortune-tellers, whom he saw as mere frauds and charlatans who used the cheap tricks of stage magic to swindle the gullible and the vulnerable. It was a campaign which was to make Houdini many enemies, destroy his friendship with one of the most popular authors of his time, and bring him all the way to the halls of the U.S. Congress.

As previously covered in our video The Last Witch of Britain, while individuals claiming to speak to the dead have existed for all of human history, the modern spiritualist movement traces its origins only as far back as 1848. In March of that year, two teenage sisters, Margaret and Kate Fox of Hydesville, New York State, began claiming they could communicate with the spirits of the dead. This communication took the form of faint, mysterious rapping sounds, heard in response to the sisters tapping or snapping their fingers. Via a complex alphabetic code, the Fox Sisters identified the spirit as belonging to one Charles B. Rosna, a travelling peddler who had been murdered by the house’s previous owner and hidden in the cellar. While a search of the cellar revealed no human remains, Margaret and Kate’s older sister, Leah, recognized the commercial potential of the girl’s abilities and became their manager, taking them on a nationwide tour financed by showman P.T. Barnum.

The tour proved a sensation, and from here the spiritualist movement quickly grew into a bona-fide religion, with its own set of codified rules and rituals. The main spiritualist practitioner was the medium, an individual – very often a woman – said to be particularly sensitive to messages from the beyond. A typical spiritualist seance would see the medium and her clients sequestered in a dark room, with the medium sometimes isolated in a separate wardrobe-like enclosure or bound to a chair to minimize distractions. When all was ready and quiet, the medium would slip into a trance and begin channeling voices from the spirit realm. Sometimes the dead communicated via rapping sounds as with the Fox sisters, while other times they spoke directly through the medium, said medium’s voice often changing to fit the spirit being channelled. Other mediums made use of automatic writing, transcribing the voices of the dead onto scraps of paper, or twin slates tied together with a piece of chalk enclosed within, on which messages from the beyond would mysteriously appear. Some seances got even wilder, with the spirits causing tables to shake, objects to fly across the room, trumpets and guitars to play eerie music, ghostly hands to pass through the participants’ hair, or a mysterious white substance called “ectoplasm” to flow out of the medium’s ears, nose, and mouth. Unsurprisingly, such experiences quickly became all the rage among well-to-do society hosts.

While in 1888 the Fox Sisters admitted that their act was a fraud – they produced the rapping sounds themselves by clicking their toe joints – it was already too late. By the early 20th Century superstar mediums like Daniel Douglas Home [“Hume”] had become fabulously wealthy and boasted such illustrious clients as Emperor Napoleon III, Tsar Alexander III, and Kaiser Wilhelm I, while the spiritualist movement attracted such luminaries as H.G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Ironically, recent advances in science and technology only helped to bolster this craze. If humans could peer into the human body with x-rays or communicate long distances via telephone or radio, the spiritualists reasoned, then why not communicate with the spirit world? Indeed, Sir Oliver Lodge, an early pioneer of radio technology, was one of the chief purveyors of spiritualism in the United States, and so-called “spirit pictures” of ghosts became all the rage among photographers. But while movement had grown steadily since the 1840s, its popularity exploded in the wake of the Great War and Spanish Flu pandemic, which combined killed more than 100 million people worldwide. Spiritualism, with its promise of direct, tangible communication with deceased loved ones, offered greater comfort to millions of bereaved families than the comparatively vague doctrines of traditional religion.

Indeed, like so many others, Harry Houdini first became interested in spiritualism due to a devastating personal loss. While early in his career he dabbled in fortune-telling and mediumship, these were merely magic acts that put food on the table. In 1913, however, Houdini’s suffered the greatest blow of his life when his mother, Cecilia Steiner, passed away. Wracked by grief, Houdini began visiting spiritualist mediums in the hopes of having one final communion with his beloved ‘mama.’ But he was to be bitterly disappointed. In every seance he attended, Houdini immediately recognized the same cheap tricks and sleight-of-hand he used in his own performances. As his wife Bess later wrote:

“Even after our numerous disappointments, whenever we visited a new medium, Houdini, with closed eyes, would join in the opening hymn, and then sit with a rapt, hungry look on his face that would make my heart ache. I knew the message that he wanted, and sometimes I felt myself tempted – but I could not betray his trust in me. So the seance would go on – the same guesses, the same trivial noises, the usual spook tricks that Houdini could do with his hands tied. The root look would fade from his face…At his next visit to his mother’s grave, I would hear him say ‘Well, Mama, I have not heard.’”

Houdini’s relationship with spiritualism hit an all-time low in July 1922 when he was invited to a seance by his friend, British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. As previously discussed in our video That Time Some British School Girls Tricked the Creator of Sherlock Holmes into Believing in Fairies, despite having created one of the smartest and most rational characters in all of literature, Doyle was a fervent believer in all things supernatural and esoteric. Like many spiritualists, Doyle’s belief was spurred by the death of his eldest son Kingsley in the Great War, though his prior experience as a physician had convinced him there were mysterious forces in the world that conventional science could not explain. Doyle’s wife Jean was a self-proclaimed medium specializing in automatic writing, and when she offered to commune with Houdini’s deceased mother, the great magician eagerly accepted. Jean Doyle proceeded to scribble out 5 pages of writing, which Houdini initially appeared to believe was the long-sought message from Cecilia. In private, however, Houdini concluded that the words could not possibly have come from his mother. For one thing, they were written in perfectly grammatical English, whereas the real Cecilia Steiner spoke only Hungarian and Yiddish. Furthermore, the message was written in a style suspiciously similar to Jean Doyle’s own voice, while each page was headed by the figure of a cross – something the Jewish wife of a rabbi was unlikely to write. Completely disillusioned and furious that grieving people around the world were being exploited by such obvious humbug, Houdini embarked on a passionate crusade to debunk the spiritualist movement once and for all, angrily declaring:

“Thirty-five years among these vultures has convinced me that they are the most contemptible and the meanest criminals that walk the earth. The confidence man, the burglar, the pickpocket, the highwayman, and others who live by robbing their fellows, must take chances. They meet their victims on even ground and triumph through their wits, their strength, or their courage.”

Houdini’s timing was fortuitous, for by this time the great magician’s star was beginning to fade. His previous career-saving hits, the suspended straitjacket escape and the Chinese water torture cell, had already grown stale, and in March 1922 Houdini found himself billed fifth in a nine-act show in Brooklyn. Hoping to revitalize his career once again, Houdini reinvented himself as a spiritualist debunker, embarking on a series of touring shows which he opened with the words:

“We laugh at the old story of witches astride broomsticks flying through space. But what could be more ridiculous than to believe that our dead appear in the form of ectoplasm through the decayed teeth or any other part of a medium’s body? Why, if our dear ones wish to communicate with us, do they resort to table flying, raps, etc., at so much per rap? Are our dead financiers? It is against all ethics to expose legitimate mysteries. But it is the duty of every citizen to expose cheats and fraud, and the most despicable cheats are the fraud mediums who use spiritualism as a cloak to prey on the gullible.”

In many ways, Houdini was the perfect man for the job, his long career in stage magic having attuned him to many of the more common tricks used by fraudulent mediums. As Houdini himself told a Los Angeles Times reporter:

“It takes a flimflammer to catch a flimflammer.”

Furthermore, Houdini was convinced that scientists were ill-suited to the task of debunking mediums, as their peculiar temperaments made them susceptible to being fooled. As Remigius Weiss, a former Philadelphia Medium, later explained:

“[Scientists] have built up a sort of theory and they treasure it like the gardener with his flowers. When they come to these mediumistic séances, this theory is in their minds. … With a man like Mr. Houdini, a practical man who has ordinary common sense and science at his disposition, they cannot fool him. He is a scientist and a philosopher.”

Houdini’s new show, which began as a simple lecture with slides, soon grew into a bona fide magic performance, with Houdini exposing the various tricks spirit mediums used to dupe their marks. Before stunned audiences, Houdini demonstrated how agile mediums could use their feet or mouths to manipulate the seance table, musical instruments, and other objects in the room without letting go of the other participants’ hands; how easily said mediums could hide accomplices around the average parlour or drawing room, and how simple cold-reading tricks could be used to work out even one’s most personal details and intimate secrets. So effective were these performances that one reviewer declared:

“It is difficult to understand how a credulous disposition towards mediums can long survive such public exposures. Here one can see Houdini reproduce the classic phenomena of the megaphone that floats, the bells that ring and the ghostly hands that brush one’s face in full sight of the audience, who see how the tricks are done – but to the bewilderment of a blindfolded man who sits with him on an isolated platform. When one watches Houdini …we are prepared to accept any marvels of this kind that mediums with their elaborate intelligence service are reported to be able to accomplish.”

Even offstage, Houdini was relentless in his pursuit of the truth, directly investigating hundreds of mediums in a bid to reveal their methods and expose them as charlatans. Some frauds were more easily uncovered than others. In particular, Houdini noted a trend among mediums of communing with the spirits of famous historical figures while getting even the most basic details of these figures’ lives and personalities hilariously wrong – for example, having George Washington speak with a cockney accent or riddling Shakespeare’s messages with grammatical errors. In a pamphlet published in 1924, Houdini recounts an especially dubious case of this phenomenon:

“On the night that the “spirit of Abraham Lincoln” began to address us, my interest mounted high, for Lincoln was my hero of heroes. I had read and studied every Lincoln book that was available at the time. I knew every published detail of the Great Emancipator’s life. And I was vaguely conscious that night of some thing about the utterances of the “spirit” that did not ring quite true. So at last I asked:

“Mr Lincoln, what was the first thing you did after your mother was buried?” “I felt very bad,” replied the “spirit” glibly. “I went to my room, and I wouldn’t speak to any one for days.”

Now, that reply probably would have been correct in a majority of cases, but it was not correct with regard to Lincoln. For Lincoln’s first act when his father had buried his dead mother was to rush off to engage a clergyman to read a burial service over her grave – an act of respect which his father had neglected! And this was certainly not an incident which Lincoln was likely to forget – in the spirit world or elsewhere.”

Lincoln was an especially popular figure among mediums on account of his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, being an avid spiritualist who regularly held seances in the White House. As a result, in 1925 Houdini used simple double-exposure techniques to create a “spirit photograph” of himself convening with Lincoln, which he presented to the late President’s son, Robert Todd Lincoln, in a bid to protect him from the predations of fraudulent mediums.

When Houdini could not immediately work out the nature of a medium’s fraud, he resorted to more ingenious tactics, such as secretly painting the medium’s props or even his own hair with ink and seeing whose hands ended up stained black. And when Houdini was unable to conduct investigations himself, he dispatched an army of private investigators to pose as clients and bait mediums with stories of non-existent life events and family members. The reports of these accomplices – one of whom, amusingly, used the pseudonym “Mr. F. Raud” – were integrated into Houdini’s shows, with Houdini arranging for both medium and investigator to be present in the audience. At one point in the performance, Houdini would order a spotlight aimed at a medium, whom he would confront with the bogus “readings” reported by one of his investigators. When the medium inevitably protested, Houdini would order the spotlight aimed at the investigator in question, who would proceed to confirm Houdini’s accusations. And so it would go until every medium in the audience had fled in humiliation. Then, with a dramatic flourish, Houdini would hold up ten $1000 New York State bonds and offer the entire $10,000 to anyone who could convincingly demonstrate genuine psychic powers. Unsurprisingly, there were no takers.

At first even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was forced to acknowledge the effectiveness of Houdini’s performances, admitting:

“Houdini’s campaign against mediums did temporary good so far as false mediums goes…the unmasking of false mediums is our urgent duty.”

However, Doyle remained steadfast in his beliefs, and between 1923 and 1924 toured the United States in parallel with Houdini delivering lectures on spiritualism. This caused considerable friction between the two friends, with Houdini growing particularly annoyed at Doyle’s belief that his own skills were the product of mystical powers:

“[Doyle] is one who firmly insists that my stage tricks are performed with the aid of spirits; that I am a psychic. Once he went so far as to ask if I was “the last word in religion and science in America.”

“Well, Sir Arthur,” I replied “not exactly that. But, if you were to build a packing-case large enough to contain me and all the American spiritualists and the scientists the uphold them, weight it with pig iron, tie us up in it and throw it into the sea, I’d be the only one that would come up. But it would be trickery that would release me,” I added.”

Houdini’s fame as medium-baiter supreme reached such heights that soon other institutions began joining in on the action. In 1924, Scientific American magazine offered a $2,500 prize to anyone who could convincingly demonstrate communication with the dead under the strictest of test conditions. Hundreds of mediums accepted the challenge, but all but one were swiftly debunked and dismissed. The only candidate who came close to winning the prize was 36-year-old medium Mina “Margery” Crandon, the wife of a prominent Boston surgeon whose talent for illusion and sleight-of-hand rivalled that of Houdini himself. Even worse, the contest’s chief organizer refused to allow Houdini to attend the controlled seances and was, according to paranormal investigator Joe Nickell, too easily swayed by Margery’s tricks:

“She was very attractive and … used her sexuality to flirt with men and disarm them. Houdini wasn’t fooled by her tricks. … [Still], she gave Houdini a run for his money.”

Fearful that the Scientific American committee would award Margery the prize over his objections, in January 1925 Houdini preemptively published a 40-page pamphlet titled Houdini Exposes the Tricks Used by Boston Medium “Margery” and staged a dramatic live exposé at Boston’s Symphony Hall. But only when Margery refused any further tests did the committee finally decide to deny her the prize.

Disturbed by how close Margery had come to duping Scientific American, Houdini decided to take his fight all the way to the highest halls of power. In February 1926, The US Congress convened four days of hearings to debate Houdini’s proposed House Resolution 8989, which would ban the practice of fortune telling in the District of Columbia. What followed was a media circus as over 300 mediums, fortune tellers, and astrologers led by spiritualist minister Jane B. Coates and astrologer Marcia Champney descended on Washington D.C. to weigh in on the future of spiritualism in America.

The hearings began on February 26, with Houdini declaring in his opening statement that:

“This thing they call Spiritualism, wherein a medium intercommunicates with the dead, is a fraud from start to finish…[mediums are all] mental degenerates or deliberate cheats.”

Then, with his usual flair for showmanship, he held up an envelope and challenged anyone in the audience to correctly determine its contents. This display was met with bemusement by the committee members, who by and large believed Houdini was overreacting. This led to numerous amusing exchanges, such as when Representative Frank Reid of Illinois correctly determined one of the phrases in the envelope, prompting Houdini to retort. “That was a guess; you are no clairvoyant!” To this Reid simply replied “Oh yes I am,” eliciting chuckles from the audience.

The other committee members largely echoed this sentiment, with Ralph Gilbert of Kentucky stating:

“I believe in Santa Claus and I believe in fairies, in a way…and [Houdini] is taking the matter entirely too seriously.”

Indeed, both the committee and the spiritualist leaders argued that spiritualism was no different from any other creed in the diverse patchwork of American religion, and that Houdini’s proposed bill would infringe upon spiritualists’ First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and religion. But Houdini was unmoved, and when spiritualist leader Jane Coates stated:

“My religion goes back to Jesus Christ. Houdini does not know I am a Christian.”

…Houdini immediately clapped back with:

“Jesus was a Jew, and he did not charge $2 a visit.”

The official hearing transcript does not record whether Houdini then proceeded to drop his mic after delivering that sick burn.

Over the next four days the hearings became increasingly theatrical and chaotic, with Houdini, the spiritualists, and the committee members hurling insults across the room and even physically brawling with each other in the lobby. The spectre of Anti-Semitism also reared its ugly head, with one spiritualist testifying, in reference to Houdini and the bill’s sponsor, New York Representative Sol Bloom:

“Judas betrayed Christ. He was a Jew, and I want to say that this bill is being put through by two—well, you can use your opinion; I am not making an assertion.”

But despite his prodigious skills as a showman and orator, Houdini soon realized that he could never defeat the First Amendment argument. But the great magician still had one more trick up his sleeve. Prior to the hearings, Houdini had dispatched private investigator Rose Mackenberg to investigate dozens of DC mediums and their clients. Her findings were shocking: dozens of high-level politicians, including senators and even presidents Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, and Calvin Coolidge regularly sought the services of mediums, with the three presidents hosting numerous seances in the White House. In fact, “Madame” Marcia Champney, leading the spiritualist delegation, had been the spiritual advisor to president Harding’s wife Florence and had allegedly predicted her husband’s election and his unexpected death in office. To Houdini, these revelations spoke for themselves: spiritualism was hardly the harmless fun or respectable creed the committee members had made it out to be, but rather a serious threat to democracy. After all, how could the American people trust their elected representatives if they were under the sway of fraudulent, unscrupulous mediums?

Ultimately, Houdini’s theatrical arguments proved fruitless, and his bill did not pass. But legal reform was never really Houdini’s goal. Rather, by bringing the issue before Congress, Houdini hoped to expose the massive fraud of spiritualism to the American people – and in this he was successful. In the wake of the hearings, belief in spiritualism in the United States dropped precipitously, and the movement would never again see the popularity it enjoyed in the immediate postwar years.

But when it comes to Houdini, the spiritualists seem to have gotten the last laugh. During the Congressional hearings, Madame Marcia publicly prophesied that the magician would be dead before end of November. On October 22, 1926, Houdini was in his dressing room at the Princess Theatre in Montreal when he was approached by McGill University student Jocelyn Gordon Whitehead. Whitehead asked Houdini if it was true that punches to the stomach did not hurt him. Houdini replied that this was true, but before he could prepare himself Whitehead delivered a series of powerful punches to the magician’s stomach. The blows ruptured Houdini’s appendix, and he soon found himself in excruciating pain and running a fever of 40 degrees Celsius. Still, he refused to seek medical attention. The next day, however,

while performing in Detroit, Houdini found himself too ill to finish the show, and was rushed to Grace Hospital where he underwent two surgeries to remove his appendix. Unfortunately the infection proved too far advanced, and Harry Houdini passed away from acute peritonitis on October 31, 1926 – just as Madame Marcia had predicted.

Despite his public crusade against spiritualism, privately Harry Houdini remained open to the idea of an afterlife and communication with the dead. He simply did not manage to find compelling evidence of it in his own lifetime. As a final experiment, following his death Houdini’s wife Bess held regular seances on the anniversary of his death, hoping to hear word from her departed husband. But after ten years she finally gave up, declaring:

“Houdini did not come through. … I do not believe that Houdini can come back to me, or to anyone.”

Yet the tradition of Houdini seances persists to this day, with devotees gathering every Halloween night in the hopes of receiving a message from the Great Beyond. Knowing Houdini, he is probably rolling in his escape-proof grave.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- That Time an Oregon Free-Love Cult Launched the Largest Bioterror Attack in US History

- What Harry Houdini’s Real Name Was

- Dan Aykroyd’s Fascination with the Paranormal and How It Inspired Ghostbusters

- Harry Houdini on Trial

Expand for References

White, April, The Famous Fight over the Turn-of-the-Century Trend of Spirit Photography, Atlas Obscura, October 29, 2021, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/houdini-conan-doyle-spirit-photography?utm_medium=atlas-page&utm_source=facebook&fbclid=IwAR3wKP_st1TdDci2XNQZh5pn9X0vF0g54mnE_pCbpFj_6SVrI6hsfMu6ZgU

Puglionesi, Alicia, In 1926, Houdini Spent 4 Days Shaming Congress for Being in Thrall to Fortune-Tellers, Atlas Obscura, October 11, 2016, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/in-1926-houdini-spent-4-days-shaming-congress-for-being-in-thrall-to-fortunetellers?utm_medium=atlas-page&utm_source=facebook&fbclid=IwAR06szQhBINHQkUNb0eEM2kNjgrgD9vhtdfi6lG2A0DQ_TlJSqaxDT96IWk

Greene, Bryan, For Harry Houdini, Seances and Spiritualism Were Just an Illusion, Smithsonian Magazine, October 28, 2021, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/for-harry-houdini-seances-and-spiritualism-were-just-an-illusion-180978944/

Houdini, Harry, How I Unmask the Spirit Fakers, 1925, https://www.all-about-psychology.com/houdini.html

Margery Pamphlet, American Experience, PBS, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/houdini-margery-pamphlet/

Gardner, Lyn, Harry Houdini and Arthur Conan Doyle: a Friendship Split by Spiritualism, The Guardian, August 10, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2015/aug/10/houdini-and-conan-doyle-impossible-edinburgh-festival

Houdini, Harry, Houdini Exposes the Tricks Used by the Boston Medium “Margery,” 1924, https://archive.org/details/BostomMediumMargery/mode/2up

The Amazing Randi & Sugar, Bert, Houdini: His Life and Art, Grosset and Dunlap, New York, 1976

The post Harry Houdini, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and the Crusade Against Spiritualism appeared first on Today I Found Out.