In the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, a massive armada set sail from southeast England and steamed south across the English Channel. Comprising more than 7,000 ships, 11,000 aircraft, and 156,000 troops, it was the largest amphibious invasion force in history. At 6:30 AM, after some 23,000 airborne troops had landed behind enemy lines, the main seaborne force stormed ashore on the beaches of Normandy. Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of France, had begun. Though the fighting was fierce, within 24 hours Overlord had achieved its main objective: securing a solid foothold in Western Europe. It was a major turning point in the Second World War, and marked the beginning of the end for Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. Within 11 months, both the Eastern and Western Allies had advanced across the continent into the heart of Germany, Hitler had committed suicide, and the war in Europe was finally brought to a close. But the stunning success of Operation Overlord relied on more than men, ships, aircraft and tanks. For months prior to D-Day, Allied intelligence agencies executed a vast, shadowy operation on a scale comparable to the actual landings themselves – a grand, elaborate deception meant to deceive the Germans as to the timing, location, and intent of the invasion and prevent Allied forces from being driven back into the sea. This is the story of Operation Bodyguard, one of the largest and most successful deceptions in military history.

In the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, a massive armada set sail from southeast England and steamed south across the English Channel. Comprising more than 7,000 ships, 11,000 aircraft, and 156,000 troops, it was the largest amphibious invasion force in history. At 6:30 AM, after some 23,000 airborne troops had landed behind enemy lines, the main seaborne force stormed ashore on the beaches of Normandy. Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of France, had begun. Though the fighting was fierce, within 24 hours Overlord had achieved its main objective: securing a solid foothold in Western Europe. It was a major turning point in the Second World War, and marked the beginning of the end for Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. Within 11 months, both the Eastern and Western Allies had advanced across the continent into the heart of Germany, Hitler had committed suicide, and the war in Europe was finally brought to a close. But the stunning success of Operation Overlord relied on more than men, ships, aircraft and tanks. For months prior to D-Day, Allied intelligence agencies executed a vast, shadowy operation on a scale comparable to the actual landings themselves – a grand, elaborate deception meant to deceive the Germans as to the timing, location, and intent of the invasion and prevent Allied forces from being driven back into the sea. This is the story of Operation Bodyguard, one of the largest and most successful deceptions in military history.

When the Western Allies began planning the invasion of France in May 1943, the task they faced was a daunting one. For protecting the western coast of Europe was the Atlantic Wall, a formidable line of fortifications stretching from the northern tip of Norway to the Spanish Border. Built by forced labourers of the infamous Organisation Todt, the wall comprised some 6,000 reinforced-concrete gun emplacements, pillboxes, and other bunkers along with millions of landmines, hundreds of kilometres of barbed wire, and thousands of steel obstacles called hedgehogs and Belgian gates meant to rip open the hulls of landing craft as they approached the beach.

But as formidable as the Atlantic wall appeared on paper, it had one crucial weakness: manpower. With the bulk of their forces tied up fighting on the Eastern Front, the Germans were desperately short of men with which to defend the West Coast of Europe. At the time of the Overlord landings, the commander of German forces in the West, Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt, had less than half a million men to defend the whole of France, consisting of the 1st and 19th Armies of Army Group G in the south and the 7th and 15th Armies of Army Group B in the north. Many of these units, fresh from the Eastern front, were exhausted from combat and had not yet regained full operational strength. Many were composed of Russian conscripts or older soldiers equipped with inferior equipment, while the German army as a whole was desperately short on fuel and vehicles, and was largely reliant on horse transport. Though the Germans knew an Allied invasion was imminent, they were unsure exactly where the blow would fall, and without sufficient troops to adequately man the Atlantic Wall along its entire 5,000-kilometre length, they faced a daunting defensive dilemma. In November 1943, Hitler appointed a new General Inspector of Western Defences: Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, whose exploits in the North African campaign had earned him the nickname “The Desert Fox.” Seeing the desperate state of German forces in the West, Rommel concluded that if an invasion could not be stopped on the beach, Germany was doomed. He thus ordered the laying of more mines and beach obstacles as well as the flooding of fields and planting of sharpened stakes known as “Rommel’s Asparagus” to deter landings by airborne troops. The German High Command, however, disagreed with Rommel’s assessment, and instead opted for a composite strategy, holding many units – including six SS Panzer divisions – in reserve inland, ready to rush to and reinforce the site of the invasion when it came.

Yet despite the poor state of the German defenders, they were still experienced combat veterans and would greatly outnumber the initial waves of Allied invaders, making Operation Overlord an extremely risky prospect. But the German manpower shortage gave the Allies an enormous advantage, for if the Germans could be fooled into thinking the invasion would land elsewhere, they would redeploy their troops to defend the false target, rendering them unavailable to counter the actual invasion. In November 1943, Colonel John Bevan, head of the London Controlling Section – the shadowy organization in charge of all Allied intelligence agencies – presented a draft deception plan at the Allied leaders conference in Tehran. Codenamed Jael after the Biblical heroine who defeated the Canaanite commander Sisera by means deception, the plan outlined elaborate series of deceptions intended to convince the Germans that the Allied invasion would be directed at multiple points along the entire coast of Europe – including Norway and the Balkans – rather than the Normandy coast. The plan appealed immensely to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who had previously written that:

“There is required for the composition of a great commander not only massive common sense and reasoning power, but also an element of legerdemain, an original and sinister touch, which leaves the enemy puzzled as well as beaten.”

After extensive revisions by British Army Colonel David Strangeways, the Jael plan was approved under the codename Operation Bodyguard, named for another of Churchill’s wartime quotes:

“In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.”

Bodyguard was not one operation but many, each designed to feed the Germans a small piece of a much larger narrative. Operations Graffham and Royal Flush, for example, were intended to convince the Germans that the Allies planned to invade Norway. As part of these operations, Allied diplomats opened negotiations with neutral Sweden, with the aim of gaining permission to land and refuel aircraft in Swedish territory during the planned invasion and convincing the Swedes to break their neutrality and side with the Allies. Meanwhile, Allied agents began conspicuously inspecting Swedish rail and port facilities, the British Treasury began investing in Scandinavian securities, and the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, launched its own deception campaign to convince the Germans that the Red Army was massing in Murmansk and Petsamo in order to invade Norway from the other side. Though the Allies had no intention of actually swaying the Swedish government, as planned, news of the negotiations soon reached Berlin via German agents in Sweden and Norway. In a classic case of knowing one’s enemy, these deceptions played on Hitler’s known paranoia regarding Norway, which supplied the majority of the iron ore he needed to fuel his war machine.

Similarly, Operations Zeppelin, Vendetta, and Copperhead sought to convince the Germans that the Allies planned to land troops in the mediterranean – specifically in the Balkans, Crete, Romania, and the south of France. Like Royal Flush, Vendetta involved Allied diplomats opening negotiations with a neutral power – in this case, Spain – leading the Germans to believe that the country might switch sides and act as a land conduit for a coming invasion. Meanwhile, Operation Zeppelin used fake radio traffic to convince the Germans that the British Ninth, Tenth, and Twelfth Armies were massing in Egypt in preparation for an invasion of the Balkans; while Operation Copperhead involved one of the strangest and unlikeliest deceptions of the entire war. In early 1944, British Army Intelligence discovered that one M.E. Clifton James, an actor serving as a Lieutenant in the Royal Army Pay Corps, bore a striking resemblance to British Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, commander of all Allied forces for Operation Overlord. James was recruited by none other than actor David Niven – then working for the Army’s film unit – and agreed to be transformed into Montgomery’s double. This proved more challenging than expected. For one thing, James smoked and drank heavily while the real ‘Monty’ was a teetotaler. James had also lost a finger during the First World War and had to be fitted with a prosthetic. Nonetheless, James eventually learned Montgomery’s speech patterns and mannerisms and in May 1944 embarked on an official tour of the Mediterranean theatre, with stops in Gibraltar, Algiers, and Cairo. The hope was that Montgomery’s apparent presence in the area would convince the Germans that the planned Allied invasion would come from the south rather than the west.

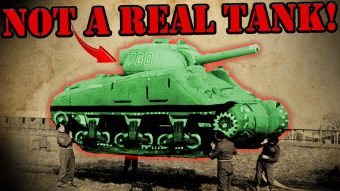

However, the largest and most elaborate component of Bodyguard was Operation Fortitude, which itself was divided into two sub-operations: Fortitude North, codenamed Skye, and Fortitude South, codenamed Quicksilver. Working in tandem with Operations Graffham and Royal Flush, Skye sought to create the illusion that a fictitious British Fourth Army numbering 250,000 men and led by General Sir Andrew Thorne was massing in Scotland for a planned invasion of Norway. To this end, armies of workmen built fake troop encampments complete with tents, barracks, trucks, and other equipment out of wood, canvas, and chicken wire. Meanwhile, hundreds of inflatable tanks made by the Dunlop rubber company and dummy aircraft built of wood and burlap were lined up in fields, while fake wooden and inflatable landing barges nicknamed “big bobs” and “wet bobs” were moored along rivers, canals, and docks, creating the illusion of a massive invasion force. So devoted were the workmen to selling this illusion that they often got carried away with the fine details. Fake landing craft were festooned with sailors’ laundry, puffed smoke from their exhaust stacks, and played dance music on their radios, while real tugboats zigzagged around the harbours to simulate regular activity. At night, arrangements of moving lamps known as “Q-lights” were used to similar effect. Where dummy tanks were deployed, weighted trailers with specially-textured wheels were towed about to create realistic tracks, while in towns where the 4th Army’s troops were supposedly billeted, local newspapers were seeded with announcement for regimental dances, sports matches, weddings, and other social events – details any German spies in the area were certain to report on. But even these fakes would not hold up to close scrutiny, so to ensure that German reconnaissance aircraft photographed the sites but didn’t get too close, antiaircraft gunners were instructed to aim poorly but keep any intruders flying above 30,000 feet.

Meanwhile, in the southeast of England, another, even larger phantom army was being conjured up as part of Operation Quicksilver. While the Germans did not know exactly where in France the Allies would land, they had their suspicions. Disturbingly, Adolf Hitler himself intuited that the most likely landing site would be Normandy, though many of his Generals disagreed, believing instead that the invasion would come at the Pas de Calais. Located at the narrowest point of the English Channel, the Pas de Calais is only 34 kilometres from the English coast, and is the shortest crossing between the two countries. It was also the most direct route into Germany’s industrial heartland in the Ruhr Valley and held a number of major ports that the Allies would need to offload men and supplies and sustain a prolonged invasion. Unknown to the Germans, the disastrous Dieppe Raid of August 19, 1942 – in which nearly 4,000 British and Canadian troops had been killed, wounded, or captured – had convinced Allied planners that attacking a well-defended port would be suicide. Instead, the Operation Overlord force would carry and assemble its own prefabricated harbours codenamed Mulberries, allowing supplies to be unloaded directly onto the invasion beaches. That the Germans expected an invasion at the Pas de Calais was a logical assumption, given that of the 179 heavy gun emplacements along the coast of France, 132 were sited in that area. The aim of Operation Quicksilver was thus to confirm the Germans’ suspicions.

As with Operation Skye, Quicksilver involved the creation of an imaginary army – in this case the First US Army Group or FUSAG, comprising 50 divisions of American and Canadian troops under the command of legendary General George S. Patton. This phantom force was stationed in Dover, directly across from the Pas de Calais, giving little doubt as to its intended target. As with its northern counterpart, Quicksilver made extensive use of fake encampments, inflatable tanks and landing craft, and other dummies to fool German reconnaissance aircraft. One of these installations was involved in an amusing incident in which an enraged bull escaped from a nearby farm and proceeded to gore one of the inflatable tanks to death – marking the one and only time FUSAG was involved in actual combat.With no less attention to detail than Operation Skye, the Quicksilver even went so far as to create distinctive insignia for each division within FUSAG, which were worn by a small contingent of soldiers who were circulated through the towns surrounding Dover, creating the illusion of a much larger force.

Perhaps the most elaborate charade of Operation Quicksilver was the construction of an entire fake oil terminal near Dover, suggesting the existence of a cross-channel pipeline to supply the invasion force.

Designed by architect Basil Spence and built of wood, canvas and sewer pipe by set decorators from Shepperton Studios, the terminal was given added credibility via official inspections by Field Marshall Montgomery, General Dwight Eisenhower, and even King George VI. Indeed, so convincing was the illusion that the German long-range guns at Cape Griz-Nez [“Gree-Nay”] occasionally opened fire on the terminal, forcing workmen to simulate realistic shell damage using flares and smoke generators.

But while the inflatable tanks, dummy aircraft, and other physical deceptions are the most memorable facet of Operation Fortitude, in reality these formed only a minor part of the overall deception. Indeed, there was little need for visual deception, for barely anyone was looking. By 1944, Allied air superiority was so complete that few German aircraft dared venture over the British Isles. And there was little risk of German spies spotting and reporting the fake armies for the simple reason that there weren’t any. Though the Germans had landed dozens of spies in Britain since the beginning of the war, every single one had been captured by or surrendered to the British Security Service, better known as MI5. More astonishingly still, the vast majority of these spies had been turned into double agents as part of a massive covert operation known as the Double-Cross System. An intelligence coup on the scale of breaking the German enigma code, the Double-Cross system gave MI5 near-total control over all human intelligence reaching Berlin from Britain, allowing them to shape the narrative of Allied war plans in any way they pleased. While dozens of double agents were employed in the lead-up to D-Day, the key players were the agents codenamed “Mutt”, “Jeff”, “Brutus”, “Tricycle”, and “Garbo.” Mutt and Jeff – real names John Moe and Tor Glad – were Norwegians landed on the coast of Aberdeenshire, Scotland in April 1941. They immediately turned themselves in and joined the Double-Cross system, feeding their German handlers intelligence on the supposed buildup of troops in Scotland as part of Operation Skye. To allay suspicions that Mutt and Jeff had been turned, MI5 staged a series of publicized sabotage attacks attributed to the pair, including a controlled explosion at a power plant.

Meanwhile, agents Brutus, Tricycle, and Garbo were employed as part of Operation Quicksilver to convince the Germans that the main Allied invasion would come at the Pas de Calais. Brutus – real name Roman Garby-Czerniawski [“Cher-nee-ov-skee”] – was a Polish Air Force officer who agreed to spy for the Germans and was sent to England, only to immediately turn himself in and work for British Intelligence. Tricycle – real name Dusko Popov – was a wealthy Serbian playboy who used his extravagant lifestyle as cover for his spying, and was one of the inspirations for the character of James Bond. Indeed, his codename was reportedly a reference to his fondness for menage-a-trois. But the real star of Double Cross was Agent Garbo, a man with a life story so audacious and unlikely it deserves its own dedicated video. Garbo – real name Juan Pujol Garcia – was a Spanish national who, at the outbreak of war, volunteered his services as a spy to the British. When he was rejected, he instead approached the German Abwehr or military intelligence, and offered to spy on the British. Given a radio and dispatched to England, Pujol instead set up shop in Lisbon and proceeded to feed the Germans a steady stream of fabricated intelligence, supplied by a completely fictitious network of 27 agents. The Germans ate up every word and counted him among their most valuable agents, even going so far as to award him the Iron Cross, Second Class. Pujol’s unlikely success soon caught the attention of British Intelligence, who finally invited him to work for them. Among the intelligence Pujol fed to the Germans was the complete composition of the Calais invasion force, which was so thoroughly accepted that German maps captured after the actual invasion showed the Allied order of battle exactly as Pujol had reported it. But Pujol’s greatest coup came on the evening of June 5, 1944, when he reported that the Canadian Army had been issued with seasickness bags and marched away, indicating that an invasion was imminent. However, Pujol’s contact in Madrid was asleep and did not receive the message until eight hours later, after the invasion was already well underway. This gamble convinced the Germans that Pujol’s intelligence was genuine, and would pay huge dividends just a few days later.

Another major element of Fortitude was the creation of fake radio traffic for the Germans to listen in on. For Operation Skye, this radio traffic was transmitted by operators stationed in Edinburgh Castle, and consisted of the mundane messages one would expect from an active Army peppered with subtle references to winter warfare, such as requisitions for skis and crampons, plans for ski training of troops, and data on the performance of tank engines in cold weather. Quicksilver’s radio traffic, transmitted from Dover Castle, was of a similar nature, but filled with oblique references to Calais. One such message fit squarely into the category of so-ridiculous-it-must-be-genuine, and quickly became legendary:

“Fifth Queen’s Royal Regiment report a number of civilian women, presumably unauthorized, in the baggage train. What are we going to do with them – take them to Calais?”

Other deceptions in the lead-up to D-Day were even more subtle. In order to destroy transport infrastructure and disrupt German logistics behind the lines, the Allied air forces launched Operation Point-Blank, a campaign of bombing raids against the French countryside. In order to maintain the pretence that the main invasion target was Calais, the Allies adopted a “two-for-one” policy whereby every raid against Normandy was matched by two raids against Calais.

It is impossible to overstate the immensity of the task and the risks the planners of Operation Bodyguard were undertaking. Every element of the grand deception had to fit together perfectly like the pieces of an enormous jigsaw puzzle, with no gaps or contradictions. If the Germans suspected even one thread of the narrative the Allies were spinning, then the whole charade would unravel and Operation Overlord would be doomed. As General Frederick Morgan, deputy chief of staff for Allied Supreme Headquarters later wrote:

“The great shadow-boxing match has to go on without a break. One bogus impression in the enemy’s mind had to be succeeded by another equally bogus. There had to be an unbroken plausibility to it all, and ever present must be the ultimate aim, which was to arrange that the eventual blow would come where the enemy least expected it, with a force altogether outside its calculations.”

Yet, against all odds, Bodyguard succeeded. The Germans, fully convinced that the Allies would land at the Pas de Calais, pulled the majority of their troops out of Normandy and stationed their reserves far behind the lines. Hundreds of thousands of troops were also retained in Norway and the Mediterranean, incapable of contributing to the defence of France. Thus, when the Allies finally hit the invasion force, they faced a much reduced defending force.

But the deceptions did not stop at Fortitude, and carried on right up to the moment of the landings and beyond. In the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy launched a series of feints codenamed Operation Glimmer, Taxable, and Big Drum. Carried out by the RAF’s famous No, 617 “Dam Busters” squadron, Glimmer and Taxable involved the deployment of one of the war’s most effective secret weapons: strips of metal foil code-named Window. Known today as chaff, Window was cut to the wavelength of the enemy’s radar, creating a strong echo that could mimic the signature of a large formation of aircraft or jam the radar entirely. Flying rotating sorties, the bombers of 617 Squadron dropped a steadily-advancing cloud of Window over the English Channel, simulating an armada of aircraft heading towards Calais. Meanwhile, in Operation Big Drum, Royal Navy motor launches steamed towards Calais towing radar reflectors suspended from balloons, simulating the advance of the invasion fleet.

Coincident to these naval and air operations, the British Army launched Operation Titanic, an effort to convince the Germans that airborne troops had landed in the Calais region. This involved aircraft dropping dummy parachutists codenamed “Ruperts” around the cities of Marigny, Fauville, and Caen.

Each Rupert was equipped with noisemakers to simulate rifle fire and a timed explosive charge to destroy the dummy. At the same time, men of the elite Special Air Service or SAS parachuted into the region and created chaos by opening fire on German troops and playing 30-minute recordings of men shouting and weapons firing. Though two aircraft were lost and eight SAS men killed, the operation was a success, sowing much confusion among the German defenders.

But while Operation Bodyguard allowed the Allies to secure a foothold across a 50-kilometre front , the success of Overlord was still not assured. Allied forces still needed time to dig in, assemble the Mulberry harbours, and begin shipping in the men and supplies needed to press deeper into France. If the Germans could mobilize their reserve forces quickly enough, they could still throw the invasion force back into the sea. Indeed, while the Germans firmly believed that the Normandy landings were merely a feint and that the real invasion would soon come at Calais, after D-Day plus two they began to waver and Hitler ordered the 1st SS Panzer Division deployed from Calais to Normandy. It is here that Juan Pujol’s – AKA Agent Garbo’s – gamble on the fifth of June paid off. On that same day, Pujol sent the following message to his handlers in Madrid:

“From the reports mentioned it is perfectly clear that the present attack (on Normandy by the 21st Army Group) is a large-scale operation but diversionary in character for the purpose of establishing a strong bridgehead in order to draw the maximum of our reserves to the area of operation to retain them there so as to be able to strike a blow somewhere else with ensured success…The constant aerial bombardment which the area of the Pas de Calais has suffered and the strategic disposition of these forces give reason to suspect an attack in that region of France which at this time offers the shortest route for the final objective of their illusions, which is to say, Berlin…”

Once again, the Germans swallowed Pujol’s lie whole and cancelled the order to redeploy the 1st Panzer Division. The unit would remain in Calais for another week, by which time the Allies had landed 326,000 men, 50,000 vehicles, and 100,000 tons of equipment on the beaches of Normandy, making the invasion force virtually impossible to dislodge. In fact, Operation Bodyguard succeeded beyond what even its planners thought possible. While London Controlling Section hoped to delay the German counterattack by 10-14 days at most, so convinced was Hitler that the real invasion was just around the corner that he did not release his reserves for a full seven weeks, giving the Allies all the time they needed to break out of Normandy and invade the rest of France.

Operation Bodyguard was one of the most audacious, elaborate, and successful deceptions in military history, paving the way for the eventual Allied victory in the West. So crucial was the operation to the ultimate success of Operation Bodyguard that in his post-war report to the Combined Chiefs of Staff, Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight Eisenhower wrote that:

“Lack of infantry was the most important cause of the enemy’s defeat on Normandy, and his failure to remedy this weakness was due primarily to the threat levelled against the Pas de Calais. This threat, which had proved of so much value in misleading the enemy as to the true objectives of our invasion preparations, was maintained after June 6, and it served most effectively to pin down the German Fifteenth Army east of the Seine, while we built up our strength in the lodgment area to the west. I cannot overemphasize the decisive value of this most successful threat, which paid enormous dividends, both at the time of the assault and during the operations of the two succeeding months. The German Fifteenth Army, which, if committed to battle in June or July, might possibly have defeated us by sheer weight of numbers, remained inoperative during the critical period of the campaign, and only when the breakthrough had been achieved were its infantry divisions brought west across the Seine—too late to have any effect upon the course of victory.”

Expand for References

Holmes, Richard, The D-Day Experience, Andrews McMeel Publishing, Kansas City, 2004

Reit, Seymour, Masquerade: The Amazing Camouflage Deceptions of World War II, Signet Books, New York, 1978

Dyck, Brent, Operation Fortitude: the Great Deception, Warfare History Network, April 2021, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/operation-fortitude-the-great-deception/

D-Day Deception: Operation Fortitude South, English Heritage, https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/dover-castle/history-and-stories/d-day-deception/

Operation Bodyguard, D-Day Info, https://d-dayinfo.org/en/preparation/operation-bodyguard/

Operation Bodyguard, Codenames, https://codenames.info/operation/bodyguard/

The post The Bizarre Story of the Massive Fake Army That Defeated the Nazis and Helped End WWII appeared first on Today I Found Out.