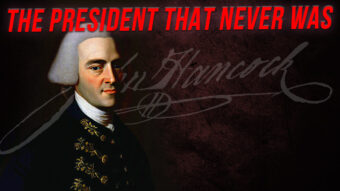

From humble beginnings to near orphan at 7, to one of the wealthiest people in America, to one of the first the British targeted as being someone no pardon would be given, to President of Congress and beyond, John Hancock led a rather interesting life as we’ve been covering in this 5 part Hancock series.

From humble beginnings to near orphan at 7, to one of the wealthiest people in America, to one of the first the British targeted as being someone no pardon would be given, to President of Congress and beyond, John Hancock led a rather interesting life as we’ve been covering in this 5 part Hancock series.

With a peace treaty finally announced in 1783 and his life no longer forfeit if the British prevailed, when he wasn’t battling health issues including severe issues with gout, John Hancock was otherwise governing the state of Massachusetts. It was in this role in 1785 when he was once again voted in as President of Congress, technically making him the first President of the United States to be elected to two non-consecutive terms given his former role as President of Congress during the early going of the war.

Unfortunately his health had deteriorated too much at this point, and he was unable to make the trip to Philadelphia to take office there directly. To add insult to injury, shortly after being elected, his 10 year old son died in an ice skating accident in January of 1786. For reference, his only other child, a daughter Lydia, had also previously died as a baby about ten years before this. Health poor, he finally resigned as President on June 6, 1786. But his work was not quite done for the new United States, having one more critical role to play.

As we’ve covered in great depth in our video The Key to Humans Humaning, after John Adams, Ben Franklin and co. successfully negotiated the end of the American Revolution with the Treaty of Paris, signed by both sides on September 3, 1783, the United States had a major problem. Despite the name, its states weren’t exactly actually united, generally out to serve their own interests first and, if convenient, those of their loose union. During the war this was less of a problem as they had pressing need to work together. Now, they didn’t.

Not only that, but in their quest to make a central government that was as purposefully weak as possible so as never to come to dominate in the way their former government did over them, they had gone too far, creating a government in the Articles of Confederation, or the so-called “league of friendship,” that had, as George Washington so famously put “no money” and no real way to get any outside of printing some that was worthless. This was a rather glaring issue for countless reasons, right down to the then complete inability for the government to pay its debts or its soldiers or for anything at all really.

The central government also had very little power it could exert over its states, or make anything happen in many cases unless all the states agreed on it, which was an extreme rarity. This was a major immediate problem when considering, for example, the aforementioned Treaty of Paris between Britain and the U.S. that ended the war and gave incredibly favorable terms to the new country. The issue was, many of the states saw little need to adhere to the treaty, and, indeed were not, and there was very little the federal government could do about it. This could have potentially blown up in the young nations’ face had Britain decided to also go back on the deal, potentially plunging the nation right back into war it couldn’t afford against a still very superior adversary, and this time perhaps not seeing the French have the United States’ back after the U.S. kind of threw them under the bus in negotiations with the British.

In short, Congress had no real power to govern anything, the states knew it, and at a certain point it even mostly ceased trying. All of this had been done very intentionally given the political minds among the colonists knew well most such attempts at similar governments in the past had ultimately devolved into some form of tyranny, whether tyranny of the majority or by those placed in power, regardless of what any laws put in place said. Not just in governments far afield or in the past, but this was something they themselves had seen with some of the then state legislatures abusing their positions in the colonies.

George Washington would write of all this, “We have probably had too good an opinion of human nature in forming our confederation.“ And, he further states, the government they had made was “a shadow without the substance”.

Thus, it became clear to all that the Articles needed, at the very least, amended heavily if the nation in some form was to survive at all. After some deliberation about this, it was decided to convene to fix the problem with delegates from each state selected to represent the people in these changes, with 70 delegates from the 13 states selected, of which 55 ultimately attended the Convention. Once there, they ultimately decided instead of modifying the Articles of Confederation, they would instead just come up with a brand new Constitution.

If you’d like the full details on the surprisingly interesting saga of the development of the U.S. Constitution and just how revolutionary it was at the time, which is often lost on us in modern times, do go check out our video The Key to Humans Humaning after you’re done watching this video. But suffice it to say for now, after a whole lot of hot and sweaty political wrangling shut up (quit literally with windows closed and all to stop eavesdropping) in the summer of 1787, enough delegates, 39, were willing to sign the completed document they came up with to approve it, despite that pretty much everyone had issues with elements of it.

And so it was that the United States had a shiny new proposed Constitution.

After everyone signed, Ben Franklin would muse while looking at a painting of the sun on the chair George Washington, who had presided over the assembly, sat in,

“Often in the course of the Session, and the vicissitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issue, [I] looked at that behind the President without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting. But now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting Sun.”

As to what happened after they all signed, according to George Washington, the remaining delegates all went out to City Tavern and had a party.

It was done.

Well, almost. It still needed ratified by the states to become official.

When it was put before Massachusetts, however, the issue of whether to ratify it was highly contentious, despite its extreme similarity to the Massachusetts Constitution from which it was partially based. Once again going back to the Articles of Confederation, many within the states at the time heavily favored independence and a loose coalition and weak central power uniting them. The new constitution was proposing the opposite of that. Others were caught up in various details of it, everything from the term length for those elected, to it not including a Bill of Rights initially, to it not abolishing slavery as the Massachusetts constitution had via John Adams’ inclusion of a Declaration of Rights which criticall had at the start- “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.”

All of these arguments were basically the same that had been made in the United States’ Constitutions’ drafting. As Ben Franklin would sum up when the document was originally approved, “There are several parts of this Constitution which I do not at present approve… I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain may be able to make a better Constitution. For when you assemble a number of men to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men, all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an Assembly can a perfect production be expected? It therefore astonishes me… to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does…Thus I consent… to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best.”

Going back to Massachusetts, when the ratifying convention first met in January of 1788, Hancock was naturally elected President of the convention, despite his ailing health which initially prevented him from attending the debates. As for his opinion on it all, he kept his cards close to his chest, including when he was first presented a copy of the proposed new constitution, he stated it was not for him, to quote, “to decide upon this momentous affair.”

However, in the early going rumors swirled that Hancock opposed the measure, allegedly in no small part as it diminished his power as governor in some ways via putting a more powerful federal government over him. Other prominent individuals such as his Lieutenant Governor Samuel Adams also seemed to be leaning that way too in the early going, though he would change his mind in the end. But before that, Samuel Adams would write to Richard Henry Lee on December 5, 1787, “I confess, as I enter the Building I stumble at the Threshold. I meet with a National Government instead of a Federal Union of Sovereign States. I am unable to conceive why the Wisdom of the Convention led them to give the Preference to the former before the latter. If several States in the Union are to become one entire Nation, under one Legislature, the Powers of which shall extend to every Subject of Legislation, and its Laws be supreme & control the whole, the Idea of Sovereignty in these States must be lost.”

With it seemingly like the ratification would not go through, Hancock finally did attend, having his servants carry him to the hall reportedly wrapped in flannels. There, on February 6, he gave a speech before the vote, throwing his support wholeheartedly behind ratification, stating,

“I am happy that my health has been so far restored, that I am rendered able to meet my fellow-citizens as represented in this Convention. I should have considered it as one of the most distressing misfortunes of my life to be deprived of giving my aid and support to a system which… cannot fail to give the people of the United States a greater degree of political freedom, and eventually as much national dignity, as falls to the lot of any nation on earth…

That a general system of government is indispensably necessary to save our country from ruin, is agreed upon all sides. That the one now to be decided upon has its defects, all agree; but when we consider the variety of interests, and the different habits of the men it is intended for, it would be very singular to have an entire union of sentiment respecting it… but, as the matter now stands, the powers reserved by the people render them secure, and, until they themselves become corrupt, they will always have upright and able rulers. I give my assent to the Constitution…

The question now before you is such as no nation on earth, without the limits of America, has ever had the privilege of deciding upon. As the Supreme Ruler of the universe has seen fit to bestow upon us this glorious opportunity, let us decide upon it; appealing to him for the rectitude of our intentions, and in humble confidence that he will yet continue to bless and save our country.”

When the votes were ultimately cast shortly after this speech, of the 355 voters, only 19 more were in favor of ratification vs against, with how close this ended up being seeing many credit Hancock choosing to side with those in favor swaying the outcome.

In the aftermath, poor health or not, Hancock’s popularity was still about as high as it could be among the masses and he easily continued to win election after election as Governor of Massachusetts.

Had it not been for his health, given his relatively young age and extreme popularity, in a likelihood John Hancock would have had a decent shot at pulling off the trifecta of not just President of the Continental Congress and then President under the Articles of Confederation, but also President under the new United States Constitution at some point, though, of course, Washington winning the first election was all but inevitable, and no one was surprised by that outcome. Speaking of that first election, while as was the custom of the time, Hancock did not campaign or even express overt interest in the office of the Presidency, he did receive 4 electoral college votes anyway, 2 from Pennsylvania, and 1 each from Virginia and South Carolina. And likely would have received significantly more if not for his boyhood friend in John Adams taking all the Massachusetts electoral votes, with Adams ultimately becoming vice president to George Washington partially because of it in 1789, and later the second President of the United States in 1797.

But whether Hancock might have secured the role for himself at some point or not, it was not to be as his health continued its rapid decline despite his relatively young age.

Ultimately John Hancock would pass away on October 8, 1793 at the age of only 56. Over 20,000 people attended his funeral, about 1 in 200 people in the United States at the time, and the date was ordered by now Massachusetts Governor Samuel Adams to be a state holiday. Hancock’s final resting place is next to his Uncle Thomas at the Old Granary Burial Grounds in Boston.

Now, if you’ve followed along in this 5 part series, you might at this point be thinking it seems a rather odd thing that the likes of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and their many prominent cohorts would be so lauded in the aftermath, yet John Hancock was largely forgotten in popular history outside of his famous signature. As one of his biographers, Harlow Unger, would write, “John Hancock’s transformation from Tory patrician to fiery rebel is one of the least-known stories of the Revolution…. [yet] he was, perhaps, the consummate American hero.”

Even John Adams in 1809 had already observed the trend and lamented that both Samuel Adams and John Hancock, two of the biggest players in the early revolution, had been so shunted to the side and, to quote Adams, “almost buried in oblivion.”

So what happened?

Well, as we can attest in doing our five video deep dive on the man, outside of countless letters pertaining to business transactions and later similar administrative letters during the Revolution, Hancock did not actually leave much in the way of personal writings for historians to gauge his thoughts, motivations, and perspectives as so many others of the founding fathers did, most prominently arguably John Adams and his son John Quincy Adams who kept daily journals for huge portions of their lives covering everything that was going on around them and their daily lives. The power of this is it allows historians to view events and decisions from the individual’s perspective to contrast from those of their political enemies and others speaking about them.

Now, if you enjoy reading about business transactions and administration, you’ll love diving into the John Hancock archives, but otherwise, he left relatively little of the rest, leaving most of what’s said about him we remember today being written by his opposition in politics. And of this, while most described him as an extremely able administrator and moderator of disputes, his propensity for insanely foppish dress and his perceived vanity from all this did not exactly endear him to many of the other leaders on a personal level, given this type of excess and his extreme wealth were generally seen as contrary to the republican ideals they were all fighting for.

Further, at least by their accounts, and to be fair you can see where it comes through in some of his own personal writings that have survived, he also seemed to enjoy to an extreme degree his popularity with the masses- in a nutshell he seems to have liked being famous, which was also seen as anti-republican to revel in such things openly. This is partially why in the early going in the United States it was tradition to not really promote yourself when running for offices like that of President, but simply to let it be known you’d accept the position if elected, and then allow your constituents to take it from there. And even if you were elected, it was expected you’d say something like you didn’t feel qualified for the job and didn’t really want it, even though in most cases the opposite was very clearly true. You just couldn’t say that. Thus, Hancock’s more open ambition, fancy dress, perceived vanity, and excessive wealth worked against his reputation with, ironically, the other elite.

As James Madison would state, “Hancock is weak, ambitious, a courtier of popularity, given to low intrigue.”

This about a man who was among the first to call the colonists to fight and was steadfast in this in the early going when it was most likely to see him hung, and he had everything to lose in his immense fortune as well even if he wasn’t arrested and executed for treason. Sure doesn’t seem weak at all.

Sam Adams would also chime in writing of the celebration Hancock held after he became governor of Massachusetts, “John Hancock … appears in public with all the pagentry of an Oriental prince. He rides in an elegant chariot. … He is attended by four servants dressed in superb livery, mounted on fine horses richly caparisoned, and escorted by fifty horsemen with drawn sabres—the one half of whom precede, and the other follow, his carriage.”

In stark contrast, and amazingly ironic if you really think about it, the masses on the whole seemed to adore John Hancock thanks to his extreme philanthropy and generous nature, amiable personality, not just towards the elite, but to the masses at any station in life, his skill as an administrator during the revolution which was critical to its early success, and his bold patriotism despite what this cost him in a number of ways when so many others in similar positions sided with the British. In short, the masses seem to have had an entirely different opinion of the man, and there’s a reason in the early going of the war there were rallying cries of “King Hancock”.

But those masses died off, and historians, with very little to work with directly from the man, mostly only accounts from his political opponents, and with much of his more significant role in the revolution being in helping to start it and, in the early going, administer it… well, let’s just say writing letters to convince some governmental body or individual to send more troops or resources or arranging the funding and outfitting the ship that sent the first diplomat to France to get that crucial aid there is not exactly as sexy as winning a major battle or drafting the declaration of independence or the Constitution. Nevermind the fact that if Hancock had not played such a prominent role in igniting the revolution in the first place, and then figuring out how to keep it going via this rather mundane administrative and mediating work, those major battle victories and everything after would not have happened.

As historian Charles Akers would sum up, “The chief victim of Massachusetts historiography has been John Hancock, the most gifted and popular politician in the Bay State’s long history. He suffered the misfortune of being known to later generations almost entirely through the judgments of his detractors, Tory and Whig.”

But perhaps John Adams, one of the most distinguished of all of his era and who knew John Hancock from boyhood, would sum him up best, writing about Hancock a couple decades after Hancock’s death, lamenting the way history remembered him. Stating in 1812,

“When will the Character of Hancock be understood? Never. I could melt into Tears when I hear his Name. The property he possessed when his Country called him, would purchase Washington and Franklin both. If Benevolence, Charity, Generosity were ever personified in North America, they were in John Hancock. What Shall I Say of his Education? his literary Acquisitions, his Travels, his military civil and political Services, his Sufferings, and Sacrifices?… I can say with truth that I profoundly admired him and more profoundly loved him.”

Five years later, in 1817 he would expound upon all this considerably, writing, “I knew Mr. Hancock from his cradle to his grave. He was radically generous and benevolent… What shall I say of his fortune, his ships? … at that time… not less than a thousand families were, every day in the year, dependent on Mr. Hancock for their daily bread. Consider his real estate in Boston, in the country, in Connecticut, and the rest of New England. Had Mr. Hancock fallen asleep to this day, he would now awake one of the richest men. Had he persevered in business as a private merchant, he might have erected a house of Medicis… [But] no man’s property was ever more entirely devoted to the public. The town had… chosen Mr. Hancock into the legislature of the province…. his mind was soon engrossed by public cares, alarms, and terrors; his business was left to subalterns; his private affairs neglected, and continued to be so to the end of his life….”

Adams concludes,

“Though I never injured or justly offended him, and though I spent much of my time and suffered unknown anxiety in defending his property, reputation, and liberty from persecution, I cannot but reflect upon myself for not paying him more respect than I did in his lifetime… But if statues, obelisks, pyramids, or divine honors were ever merited by men, of cities or nations… John Hancock deserved these from the… United States….

James Otis, Samuel Adams, and John Hancock were the three most essential characters [in the revolution]; and Great Britain knew it, though America does not. Great and important and excellent characters, aroused and excited by these, arose in Pennsylvania, Virginia, New York, South Carolina, and in all the other States, but these three were the first movers, the most constant, steady, persevering springs, agents, and most disinterested sufferers and firmest pillars of the whole Revolution.”

The post Hancock: United at Last appeared first on Today I Found Out.