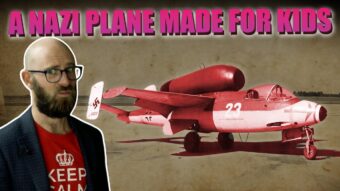

By the winter of 1944 and 1945, the German Third Reich was in dire straits. Adolf Hitler’s final offensive in the Ardennes had failed, the Soviet Red Army was driving ever closer to Germany’s borders, and day and night Allied bomber aircraft were pummelling German cities into smoking rubble. With the end in sight, the Nazi government hastily assembled a desperate, last-ditch force to fight the final battle for the Fatherland: the Volkssturm, a citizens’ militia composed of young boys and old men. Poorly trained and armed with a motley assortment of leftover weapons, Volkssturm units were derisively nicknamed “casseroles” by the regular Army, as they were full of “old meat and green vegetables”. Little more than cannon fodder against the better armed and trained Allied forces, the Volkssturm was emblematic of the suicidal fanaticism that typified the dying days of the Third Reich. But the madness went even further, for the youth of Germany were not only expected to face off against Russian tanks on the streets of Berlin, but shoot down waves of American bombers using crude wooden fighter jets. This is the story of the Heinkel He-162 Volksjäger, Nazi Germany’s last-ditch fighter designed to be flown by children.

By the winter of 1944 and 1945, the German Third Reich was in dire straits. Adolf Hitler’s final offensive in the Ardennes had failed, the Soviet Red Army was driving ever closer to Germany’s borders, and day and night Allied bomber aircraft were pummelling German cities into smoking rubble. With the end in sight, the Nazi government hastily assembled a desperate, last-ditch force to fight the final battle for the Fatherland: the Volkssturm, a citizens’ militia composed of young boys and old men. Poorly trained and armed with a motley assortment of leftover weapons, Volkssturm units were derisively nicknamed “casseroles” by the regular Army, as they were full of “old meat and green vegetables”. Little more than cannon fodder against the better armed and trained Allied forces, the Volkssturm was emblematic of the suicidal fanaticism that typified the dying days of the Third Reich. But the madness went even further, for the youth of Germany were not only expected to face off against Russian tanks on the streets of Berlin, but shoot down waves of American bombers using crude wooden fighter jets. This is the story of the Heinkel He-162 Volksjäger, Nazi Germany’s last-ditch fighter designed to be flown by children.

As the Allied bombing offensive over Germany intensified throughout 1943 and 1945, Nazi planners turned to a series of increasingly sophisticated “wonder weapons” in a desperate attempt to stem the tide. These weapons included guided surface-to-air missiles like the Messerschmitt Enzian and Henschel Schmetterling; jet fighters like the Messerschmitt Me-262 Schwalbe, and rocket fighters like the Messerschmitt Me-163 Comet. However, not only were these weapons resource-intensive to produce in the large quantities needed, but most could only be flown by experienced pilots – something Germany had in short supply. So, on September 10, 1944, the Reich Air Ministry or RLM put out a call for the development of a lightweight “emergency fighter”. According to the RLM specifications, the aircraft had to be powered by a single BMW 003 turbojet engine, weigh under 2 metric tons, use a minimum of strategic materials like steel and aluminium, and be easy to mass-produce. Minimum performance was set at 750 kilometres per hour (or 466 mph) top speed with a takeoff roll of no more than 500 metres and a flight endurance of at least 30 minutes. Armament was to be two 20mm cannons with 100 rounds per gun or two 30mm cannons with 50 rounds per gun. Most crucially, however, the aircraft had to be easy to fly with minimal training, allowing members of the Hitler Youth to fly it into combat. Proposals were to be submitted no later than September the 20th, and the winning entry ready to enter production by New Year’s 1945. This ambitious and foolhardy program soon became known as the Volksjäger – the “people’s fighter.”

The Volksjäger program was vehemently opposed by leading figures in the German Luftwaffe including Generalleutnant Adolf Galland, who feared it would divert resources from more promising aircraft like the Me-262. This view was also shared by many in the German aviation industry, such as engineers Willi Messerschmitt and Kurt Tank. However, since the project had the support of Reichsmarschall Herman Göring and Minister of Armaments Albert Speer – both high-ranking figures in the Nazi government – these objections were ignored.

Nearly every aircraft manufacturer in Germany submitted a proposal for the Volksjäger program, but only two made RLM’s short list: Blohm and Voss and Heinkel. Blohm and Voss’s proposal, the P.211, was remarkably advanced for the time, with a fuselage-mounted engine reminiscent of post-war jet fighters like the American F-86 Sabre and Soviet MiG-21. The initial design even included swept-back wings for extra speed, though for ease of production these were soon changed to simpler straight wings.

Unfortunately for Blohm und Voss, however, Heinkel had already been working on a lightweight fighter for some time. In July 1944, Siegfried Günter, head of Heinkel’s project office, issued a report to his senior managers summarizing the state of the German air forces and the ideal design requirements for fighter aircraft going forward: “In addition to numerical ratios, the attainment air superiority also depends on flight performance. If enemy jet single-seaters are encountered, the superiority of the Me 262 cannot be relied upon due to its conventional design with unswept wings and the arrangement of the motor near the ground – which makes fuel consumption high and the range short. For this reason, it is necessary to limit yourself to a single-seater aircraft with the least possible equipment and the largest proportion of fuel in the total weight.”

This aircraft design became known as the P 1073 Strahljäger, and was calculated to have a maximum speed of 1,010 kilometres per hour and a maximum range of 1,000 km using Heinkel’s own He S-11 turbojet. But when the RLM issued its Volksjäger specifications on September the 10, Heinkel quickly adapted the P 1073 design to use the specified BMW 003 engine and submitted it to the competition the following day. Thanks to this head start – as well as a measure of political lobbying, Heinkel ultimately won the competition, and signed a contract with RLM to deliver 1,000 Volksjägers by April of 1945 and 2,000 by May. The design was officially designated the He-162 Spatz or “Sparrow”, though many sources incorrectly refer to the aircraft as the “Salamander” – actually a codename for its wing structure.

Designed by Siegfried Günter and Karl Schwärzler, the He-162 was a radical-looking aircraft. Its single jet engine was mounted in a streamlined pod above the fuselage, with the intake just above and behind the pilot’s head. This, along with the aircraft’s short tricycle landing gear, was intended to provide easy access to the engine for maintenance – a useful feature since the service life of early jet engines was measured in hours. While the fuselage was made of metal, to conserve strategic materials the short wings and twin tail – chosen to clear the engine exhaust – were built of laminated wood. Further, as bailing out conventionally was likely to result in the pilot being sucked into the engine intake, the He-162 was among the first combat aircraft to be fitted with an ejection seat, which launched the pilot clear of the cockpit using a small explosive cartridge.

Two versions of the aircraft were initially planned: the He-162 A-1 bomber destroyer armed with two 30mm MK-108 cannons, and the He-162 A-2 air superiority fighter armed with two 20mm MG-151’s. That said, the recoil of the MK-108s proved too powerful for the tiny airframe, so ultimately the MG-151s were used instead. Heinkel also came up with a number of follow-up models, including the He-162A-3 with a strengthened nose to take the recoil of the MK-108s, the He-163B-1 with a more powerful engine and greater endurance, the He-162S tandem-seat glider for training Hitler Youth pilots, and a number of variants powered by simpler and cheaper pulse-jet engines. However, due to lack of time and resources, only the basic A-1 model was ever mass-produced.

Incredibly, just 74 days passed between Heinkel accepting the RLM contract on September 23 and the He-162 prototype’s first test flight on December 6. This took place at Schwechat airfield near Vienna, with Heinkel test pilot Gotthold Peter at the controls. At first all went well, until, 20 minutes into the flight, a landing gear door fell off, forcing Peter to land immediately. The failure was soon traced to a faulty glue bond, a problem that would plague the aircraft throughout its short career. Nonetheless, the test was deemed a success, with the He-162 reaching an impressive top speed of 840 kilometres per hour (or 521 mph) at an altitude of 6,000 metres or about 20,000 ft. However, it quickly became apparent that the Nazi government’s plans to crew the Volksjäger with Hitler Youth was a fanatical pipe dream; while extremely fast and highly manoeuvrable, the He-162 proved tricky even for an experience pilot like Peter to handle, exhibiting significant lateral instability. And even bigger problems appeared four days later as Gotthold Peter took to the air to demonstrate the He-162 before Nazi Party officials. While making a high-speed pass over the airfield, the wing came partly unglued and shed an aileron, sending the aircraft crashing to the ground and killing Peter instantly.

Despite this setback, production of the He-162 carried on as planned. Indeed, such was the Nazis’ desperation to get the Volksjäger into combat as soon as possible that mass production began even before the first prototype had flown, with modifications derived from the flight testing program being applied directly on the assembly line. Among these were strengthening of the wing structure and the addition of turned-down wingtips to correct some of the aircraft’s lateral stability problems.

While the first 31 He-162s were produced at the Heinkel plant in Vienna, the ongoing Allied bombing campaign forced Heinkel to disperse production of components to small shops and factories all over Germany. Final assembly took place at the Heinkel plant in Merienhe, the Junkers plant at Bernberg, and the underground Mittelwerk factory at Nordhausen in the Harz Mountains. Here, the aircraft were assembled by forced labourers from the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, under the brutal watch of the SS. Incidentally, Mittelwerk also assembled the infamous V-2 ballistic missile, 3,000 of which would rain down on England and Belgium between September 1944 and March 1945, killing over 9,000 people.

This brings us to February of 1945 when the Luftwaffe formed Erprobungskommado 162, an evaluation unit commanded by Oberstleutnant Heinz Bär, an experienced fighter pilot with 200 confirmed kills. Based at Rechlin Airfield in southern Germany, the unit received the first batch of 46 He-162s and spent the next two months familiarizing themselves with the aircraft’s handling characteristics. Meanwhile, the first operation unit He-162 unit, Jagdgeschwader I, was formed at Parchim, near the Heinkel factory at Marienhe. However, as preliminary flight testing had indicated, the He-162 proved tricky to fly – especially on takeoff and landing – leading to many accidents. As pilot Harald Bauer later recalled:

“When we started out in February and March it was a very tough, cold winter at the time, and they had ploughed runways with ice banks forming at the sides. During my short period [at the Heinkel Works] from December 44 to March 45, we started out with 65 people, and when I took off on my last test flight, we were 5 left of the original group. None of them died in combat; all of them [died] either [by] breaking out on landing or breaking out on takeoff (hitting the ice on either side of the runway). And then a sweeper truck came and swept the remains into a big hole.”

Things didn’t exactly improve when, on April 7, 1945, just as JG-I was approaching combat readiness, Parchim airfield was bombed by American B-17 Flying Fortress aircraft, forcing the unit to move to nearby Ludwigslust airfield. A week later they moved again to Leck in Schleswig-Holstein, near the Danish Border, where the He-162 finally saw combat for the first time. On April 19, the type scored its first victory when an He-162 of JG-I shot down a British Hawker Tempest fighter. However, the German pilot was soon shot down himself by another Tempest while returning to base. The following day, another He-162 pilot performed one of the first successful combat ejections in history. While his reason for bailing out is not recorded, given the He-162’s half-hour endurance it is likely he simply ran out of fuel. Indeed, while He-162 pilots managed to score a handful of victories before the end of the war, this came at the cost of 13 aircraft and 10 pilots – most being lost to landing or takeoff accidents and engine failures.

Fast-forward to early May, shortly after Adolf Hitler managed to take out Hitler in Berlin, Erprobungskommando 162 was formed into an operational unit under the command of Adolf Galland. But this was too little, too late, for a week later Germany surrendered and Galland’s men burned their aircraft to prevent them falling into enemy hands. Other units, however, gladly handed over their mounts, giving Allied pilots and engineers examples to evaluate the strange little jet. Thankfully, the Nazi Party’s mad scheme to send swarms of Hitler Youth pilots against the might of the Allied air forces never came to pass. If it had, it is likely that accidents and mechanical failures would have killed most of these boy warriors before they ever saw the enemy.

That said, Allied flight testing later revealed that overall, the He-162 was an exceptional combat aircraft, whose most glaring flaws were mostly just the result of rushed development, poor-quality materials, and the inexperience of its pilots. That the aircraft turned out as good as it did under such desperate conditions is a testament to the skill and ingenuity of Siegfried Günter and his design team at Heinkel. Today, seven He-162s survive in museums around the world, the strange little hunchbacked fighters serving as silent reminders of the fanaticism and desperation that overtook Germany in the final days of the Third Reich.

Expand for References

The High-Performance Aircraft Heinkel He-162 from 1945, Deutsches Technikmuseum, September 27, 2011, https://web.archive.org/web/20120529231119/http://www.sdtb.de/Medieninfo-Heinkel-He-162.1921.0.html

Heinkel He 162 A-2 Spatz (Sparrow), National Air and Space Museum, https://www.si.edu/object/heinkel-he-162-2-spatz-sparrow%3Anasm_A19600321000

Goebel, Greg, Heinkel He 162 Volksjaeger, Air Vectors, January 1, 2023, http://www.airvectors.net/avhe162.html

Heinkel He 162 Jet Fighter Test Pilot, PeninsulaSrsVideos, www.youtube.com/watch?v=xmJqjx9VVKM

Heinkel He 162 “People’s Fighter”, http://balsi.de/Weltkrieg/Waffen/Flugzeuge/he162.htm

The post The Jet the Nazis Designed to Be Flown By Children appeared first on Today I Found Out.