The world of aviation abounds with thousands of unique aircraft designs, from tiny ultralights to giant military transports. Yet no matter how advanced or outlandish these designs get, nearly all fall into one of only two basic categories: fixed wing or rotary wing. But the history of aviation, like that of all technologies, is riddled with false starts and dead ends, and once upon a time the landscape of aircraft design was considerably more diverse. For example, well into the 20th Century many inventors believed that flapping-wing ornithopters were a viable means of human flight, while in the 1920s it seemed like giant gas-filled airships were the future of commercial aviation, offering a more comfortable and luxurious experience than airliners of the time. By the end of the 1930s, a series of high-profile disasters including the crash of the British R101 and German Hindenburg (which by the way despite the plummeting firey ball, over half the passengers actually survived that one), this all brought the age of the giant airship to an abrupt close, ceding the future of flight to the airplane and eventually the helicopter. But largely forgotten among aviation’s many false starts is a bizarre effort to achieve manned flight using giant powered kites. And the unlikely figure behind this eccentric quest was none other than legendary inventor Alexander Graham Bell.

The world of aviation abounds with thousands of unique aircraft designs, from tiny ultralights to giant military transports. Yet no matter how advanced or outlandish these designs get, nearly all fall into one of only two basic categories: fixed wing or rotary wing. But the history of aviation, like that of all technologies, is riddled with false starts and dead ends, and once upon a time the landscape of aircraft design was considerably more diverse. For example, well into the 20th Century many inventors believed that flapping-wing ornithopters were a viable means of human flight, while in the 1920s it seemed like giant gas-filled airships were the future of commercial aviation, offering a more comfortable and luxurious experience than airliners of the time. By the end of the 1930s, a series of high-profile disasters including the crash of the British R101 and German Hindenburg (which by the way despite the plummeting firey ball, over half the passengers actually survived that one), this all brought the age of the giant airship to an abrupt close, ceding the future of flight to the airplane and eventually the helicopter. But largely forgotten among aviation’s many false starts is a bizarre effort to achieve manned flight using giant powered kites. And the unlikely figure behind this eccentric quest was none other than legendary inventor Alexander Graham Bell.

Born in Scotland in 1847, Bell is perhaps best remembered for his work on the telephone, which he patented in the United States in 1876. However, Bell’s creative genius knew few bounds, spanning fields as diverse as architecture, medicine, genetics, and – his lifelong passion – teaching the deaf to speak. Among his numerous inventions were the first metal detector, a precursor to the iron lung, an improved version of Thomas Edison’s phonograph called the Graphophone, and a hydrofoil boat that in 1919 set a world speed record of 113 kilometres an hour. In 1893, flush with cash from the telephone, Bell and his wife Mabel built a palatial estate at Baddeck on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, which they dubbed Beinn Bhreagh [“Ben Vree-ah”] – Gaelic for “Beautiful Mountain.” In addition to the large mansion, the grounds included a variety of facilities dedicated to Bell’s wide range of scientific interests, such as an observatory, a sheep farm for studying genetics, and a boat house where Bell developed hydrofoils. That same year, Bell would develop a new obsession: human flight, research on which was beginning to pick up steam all around the world. His entry into this exciting new field was celebrated by his fellow scientists and inventors, including meteorologist Henry Clayton, who wrote in 1903:

“It is fortunate for those interested in aeronautics and the exploration of the air that Professor Alexander Graham Bell has joined the band of experimenters and is lending his inventive genius to the cause.”

Bell began his experiments by building a helicopter-like device with rotating wings, powered by a miniature steam boiler. Though the contraption successfully flew across a room, it was impossible to control and like all steam-powered machines could not be scaled up to a level needed for manned flight, steam engines simply having too low a power-to-weight ratio. Nonetheless, Bell was optimistic, writing to his wife:

“I have the feeling that this machine may possibly be the father of a long line of vigorous descendants that will plough through the air from Beinn Bhreagh to Washington. And perhaps revolutionize the world! Who can tell? Think of the telephone!”

But the course of Bell’s research would soon be diverted by the work of two men. The first was German inventor Otto Lilienthal, who between 1891 and 1896 performed hundreds of successful, controlled flights in homemade, bird-like hang gliders. The second was Australian Lawrence Hargrave, who in 1893 invented the box kite, a design so efficient Hargrave was able to use three kites to lift himself 16 feet off the ground. Inspired by Hargrave, in 1894 Bell built a giant box kite 14 feet long and 10 feet wide, which he referred to as “a monster, a jumbo, a full-fledged white elephant.” Indeed, it was so large an entire wall of the kite house at Beinn Bhreagh had to be dismantled to get the kite outside. And true to Bell’s description, it proved too heavy to fly in even the strongest winds.

Then, on August 10, 1896, Bell received shocking news: Otto Lilienthal had been killed when a stray gust of wind caused his glider to stall and crash, breaking the inventor’s spine. This event profoundly impacted Bell’s outlook on manned flight, as he wrote in his diary:

“A dead man tells to tales; he advances no further. How can ideas be tested without actually going into

the air and risking one’s life on what may be an erroneous judgement?”

This further pushed Bell to think that kites were the answer. In Bell’s conception, a powered kite did not need to land; instead it could be brought into the wind and moored to the ground by a cable, allowing the pilot to climb down via a rope ladder. And in an emergency, a kite would not violently crash but rather float gently to the ground. At least, so he thought. It was, Bell concluded, the only way for humans to achieve flight safely, and with this in mind he threw himself into research on manned kites.

The main technical hurdle facing Bell was that of scale. When a kite is scaled up, its surface area increases by the square of its length while its volume – and thus its weight – increases by the cube, meaning the kite quickly becomes too heavy to lift itself off the ground. After much experimentation, Bell came up with an elegant solution: the tetrahedral cell, a 3D construction of four triangular faces which could be combined into much larger, modular structures. As multiple cells could share the same structural member, the weight of the kite grew at a much slower rate than conventional designs when scaled up. It was also immensely strong. As Bell explained:

“It is not simply braced in two directions in space like a triangle, but in three directions like a solid.”

Bell’s finalized cell design, built first of black spruce and later aluminium tubing, was 10 inches to a side and covered on two sides with red silk, chosen because it was lightweight, airtight, and photographed well in black-and-white.

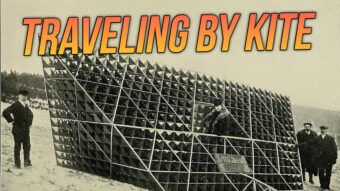

Over the next ten years Bell and his assistants test-flew dozens of different sizes and shapes of tetrahedral kites, including rings, prisms, and hexagons. This research reached its peak in 1905 with the construction of the largest kite the world had ever seen: the Frost King. So-named because Bell’s daughter Susie had recently married a man named Jack Frost, the kite measured 30 feet long, contained 1300 cells and had 400 square feet of lifting surface, yet weighed only 165lb. Nonetheless, Bell was forced to wait months for winds strong enough to lift it.

That wind finally came in November 1905 when a powerful gale blew through Baddeck. Bell excitedly rushed out to fly the Frost King, only to discover that his assistants, unwilling to row across the choppy lake, had decided to remain home. Bell, already depressed by the death of his Father two months before, was devastated by the apparent missed opportunity. After writing a note disbanding the kite-flying team, he retreated to his study to sulk. However, his devoted wife Mabel was having none of it. Realizing that her husband was squandering ideal flying conditions, she rounded up the rest of the domestic staff – including Bell’s manservant Charles Thompson, secretary Arthur McCurdy, and coachman Neil McDermid – and together this makeshift team carried the Frost King out onto the testing field. The flight was a resounding success, the kite producing so much lift it accidentally hoisted McDermid nearly 30 feet off the ground. Of the event, Mabel would later write:

“The experiment was so satisfactory, that it demonstrates that this form of kite could sustain a much greater load than he had dared hope.”

However, by this time Bell’s obsession with kites had begun to worry his family and colleagues, many of whom saw the experiments as a technological dead end. For example, a few years earlier, after visiting Beinn Bhreagh in 1901, Bell’s former student Helen Keller opined:

“Mr. Bell has nothing but kites and flying machines on his tongue’s end. Poor dear man, how I wish he would stop wearing himself out in this unprofitable way.”

Bell, however, dismissed his critics as having missed his point, writing:

“The word ‘kite’, unfortunately, is suggestive to most minds of a toy just as the telephone at first was thought to be a toy.”

Ironically, Bell would later suggest developing the tetrahedral kite into a toy, the sales of which he believed could finance the construction of larger machines. In a letter to Mabel, he claimed that if only 1/4 of all American children bought this toy, he could raise over $100,000 (about $3.1 million today). Apparently finding her husband’s logic rather dubious, Mabel instead encouraged him to patent the tetrahedral method of construction and find other applications for it. Towards this end, in August 1907 Bell erected an observation tower on the highest point of Beinn Bhreagh. Composed of three tetrahedral trusses arranged to form one large tetrahedron, the tower was highly efficient structurally and could be easily erected from the ground without the need for cranes or scaffolding. Today, this method of construction is known as an octet frame, and is widely used in applications as diverse as sports stadiums and the International Space Station.

Nonetheless, aeronautical science was rapidly passing Bell by. Among Bell’s many scientific colleagues was Samuel Langley, President of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington and main rival to the Wright Brothers in the race to achieve controlled, powered, manned flight. On May 9, 1896, Bell was present when Aerodrome #6, a scale model of Langley’s manned aircraft design, was launched from a houseboat on the Potomac near Quantico, Virginia, and flew for an extraordinary 1 minute, 20 seconds, covering a distance of over 3,000 feet. This demonstration made it clear to Bell that manned flight was just around the corner, and that it would be achieved not by kites, but by winged aircraft.

Thus, at Mabel’s suggestion, on October 1, 1907, Bell formed the Aerial Experiment Association, a group dedicated to advancing aviation technology. Backed by a $20,000 grant from the sale of some of Mabel’s family property, the AEA’s members comprised Bell, engineers J.A.D. McCurdy and Frederick Casey Baldwin, U.S. Army Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge, and engine designer Glenn Curtiss. Despite being nearly four years since the Wright Brothers’ historic first flight on December 17, 1903, Bell insisted on carrying on with his kite research. This resulted in the construction of the Cygnet, a man-carrying kite composed of 3400 tetrahedral cells and fitted with a short stabilizer tail and a pair of pontoons. On December 6, 1907, with Lt. Selfridge at the controls, the Cygnet was towed out onto Bras D’Or lake by the steamer Blue Hill. As the steamer accelerated, the kite lifted gracefully into the air, reaching a maximum height of 168 feet. She remained aloft and stable for a full 7 minutes until, suddenly, disaster struck. Selfridge was supposed to cast off the towline as soon as the aircraft touched down on the water, but nestled in among the kite cells, his visibility was limited and by the time he realized he had landed the Cygnet was dragged through the water and torn to pieces. Though Selfridge managed to disentangle himself from the wreckage and swim to the surface, the incident was an eerie portent of things to come. On September 17, 1908 Thomas Selfridge would be killed during a demonstration flight with Orville Wright over Fort Meyer, Virginia, becoming the first person in history to die in a plane crash.

Despite this setback, Bell proceeded with the construction of the improved Cygnet II, which featured a wheeled undercarriage and Curtiss V-8 engine. It proved a dismal failure, as did the even larger Cygnet III, which, despite using a more powerful engine, only managed to lift itself two feet off the ground. During a test flight on March 19, 1912, the tetrahedral structure failed and the aircraft was destroyed beyond repair. This failure finally convinced Bell that this approach to manned flight was a dead end, and he abandoned his kite experiments. However, kites would continue to hold a special place in the inventor’s heart. When Bell died in 1922, he was buried in a coffin lined with red kite silk.

But the AEA’s efforts had not been in vain. While Bell remained in Baddeck, the rest of the team moved their operations to Glenn Curtiss’ headquarters in Hammondsport, New York, where they constructed a series of increasingly sophisticated aircraft. On March 12, 1908, their first design, Red Wing, flew 319 feet over Lake Keuka. Red Wing was soon followed by White Wing, which introduced an important new innovation: hinged ailerons on the wingtips for roll control. Previous aircraft, including the Wright Brothers’ 1903 Flyer, had induced roll by physically distorting the wing tips, a system known as wing warping. Today, ailerons are standard equipment on nearly all aircraft. The AEA’s next aircraft, June Bug, was even more sophisticated, introducing special paint called dope to seal the wing fabric and steerable tricycle undercarriage. On July 4, 1908, June Bug achieved another first when it flew a distance of 5,090 feet, winning the Scientific American Trophy for the first flight over 1 kilometre.

The AEA’s last and most famous creation was the Silver Dart, which incorporated all the lessons learned from the group’s previous aircraft. Built largely of bamboo and wood and powered by a 50 horsepower Curtiss V8 engine, the aircraft was named after the metallic balloon dope used to seal its wing fabric.

On February 23, 1909, with J.A.D. McCurdy at the controls, the Silver Dart made history when it lifted off the ice of Bras D’Or Lake, becoming the first manned aircraft in the British Empire to make a controlled, heavier-than-air powered flight. The aircraft would be flown another 30 times over the next month, making its longest flight of 11 minutes on March 9. This flight brought an end to the AEA’s activities, the association being officially disbanded on March 31, 1909. In less than a year and a half, this small band of pioneering inventors and dreamers had succeeded in turning the aeroplane from a rickety, precarious contraption into a viable transport technology.

While Alexander Graham Bell’s quixotic obsession with giant kites might seem quaint and foolish to us today, it is important to remember that at the time, nobody could have predicted what path the brand-new technology of flight would take. It was an exciting era of endless possibilities, when anything seemed possible and the sky really was the limit.

Expand for References

Gray, Charlotte, Reluctant Genius: the Passionate Life and Inventive Mind of Alexander Graham Bell, Phyllis Bruce Books Perennial, 2007

In Pictures: Tetrahedral Kites by Alexander Graham Bell, Lomography, September 25, 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20180503180547/https://www.lomography.com/magazine/333099-in-pictures-tetrahedral-kites-by-alexander-graham-bell

Alexander Graham Bell’s Tetrahedral Kites (1903-09), The Public Domain Review, https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/alexander-graham-bell-s-tetrahedral-kites-1903-9

Nemo, Leslie, Alexander Graham Bell Goes and Flies a Kite – For Science, Scientific American, January 21, 2021, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/alexander-graham-bell-goes-and-flies-a-kite-for-science/

Lucarelli, Fosco, Structures to Let Man Fly: Bell’s Tetrahedral Kites, Socks, February 4, 2014, https://socks-studio.com/2014/02/04/structures-to-let-man-fly-bells-tetrahedral-kites/

After the Telephone – Tetrahedral Kites, Airplanes, and Hydrofoils, Best Breezes, http://best-breezes.squarespace.com/alexander-graham-bell-tetrah/

The post Dustbin of History: That Time the Inventor of the Telephone Dedicated His Life to the Creation of Manned Giant Kites appeared first on Today I Found Out.