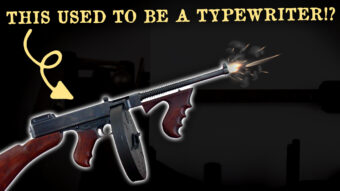

At 10:30 AM on February 14, 1929, a rattle of gunfire echoed through Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood. Seven men, Irish members of Chicago’s North Side Gang, had been gunned down in a garage at 2122 North Clark Street by assailants dressed in police uniforms. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre would go down as one of the most brutal chapters in the city’s Prohibition-Era gang wars, and though the perpetrators were never definitively identified, suspicion immediately fell on the North Side Gang’s greatest rival, the Chicago Outfit, headed by legendary mob boss Al Capone. In addition to damaging the reputation of Capone – who until that point had been seen by many as a philanthropist and even a modern-day Robin Hood, the massacre brought notoriety to one of the instruments used in its commission, a weapon which has come to define the “Roaring 20s” and remains one of the most recognizable firearms in history. This is the story of the iconic Thompson Submachine Gun – AKA the “Tommy Gun.”

At 10:30 AM on February 14, 1929, a rattle of gunfire echoed through Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood. Seven men, Irish members of Chicago’s North Side Gang, had been gunned down in a garage at 2122 North Clark Street by assailants dressed in police uniforms. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre would go down as one of the most brutal chapters in the city’s Prohibition-Era gang wars, and though the perpetrators were never definitively identified, suspicion immediately fell on the North Side Gang’s greatest rival, the Chicago Outfit, headed by legendary mob boss Al Capone. In addition to damaging the reputation of Capone – who until that point had been seen by many as a philanthropist and even a modern-day Robin Hood, the massacre brought notoriety to one of the instruments used in its commission, a weapon which has come to define the “Roaring 20s” and remains one of the most recognizable firearms in history. This is the story of the iconic Thompson Submachine Gun – AKA the “Tommy Gun.”

In 1884, modern warfare changed forever when American inventor Hiram Maxim patented the first reliable, self-loading machine gun. With a rate of fire of 600 rounds per minute, the Maxim Gun allowed its operator to deliver an unprecedented volume of fire, especially compared to the single-shot and bolt-action infantry rifles of the era. This firepower allowed the various European colonial powers to cut swath through native populations during the late 19th-Century “Scramble for Africa,” leading writer Hillaire Belloc to famously quip in his 1898 poem The Modern Traveller:

Whatever happens, we have got

The Maxim Gun, and they have not

Unfortunately, Maxim’s invention proved equally effective against modern armies, as military planners would quickly learn to their dismay as the world marched off to war in August 1914. Along with artillery – the true killer of the Great War – the Maxim and other heavy machine-guns helped turn the Western Front into a bloody stalemate of trench warfare, in which thousands of men at a time were cut down in futile assaults to capture just a few dozen metres of ground. Almost from the moment the front lines began to stagnate, military planners on all sides began searching for “wonder weapons” that could help break the deadlock. This search produced a variety of technologies still used in warfare today, including tanks, aerial bombardment, and flamethrowers But a fundamental problem still remained: the average infantryman, armed only with a bolt-action rifle, lacked sufficient firepower to adequately exploit a breakthrough.

One proposed solution was the combat shotgun, introduced to the Western Front by the American Expeditionary Force in 1917. Unlike regular combat rifles, pump-action shotguns like the Winchester 1897 or 1912 could easily be maneuvered in the confines of a trench and deliver a withering volume of fire, theoretically allowing an assaulting soldier to jump down into an enemy trench and “hose it down” within seconds. The American deployment of shotguns famously elicited diplomatic protests from the Imperial German government, who declared their use a war crime and threatened to summarily execute any soldier caught carrying one. The Americans, finding this rather rich coming from the nation that had introduced flamethrowers, unrestricted submarine warfare, and chemical warfare, called the Germans’ bluff and threatened reprisals should they ever make good on their threat and nothing ever came of the incident. In the end, however, shotguns proved far less effective in combat than anticipated, largely due to problems with ammunition. WWI-era shotshells had paper hulls, which tended to absorb moisture and swell, preventing them from effectively feeding in the shotgun mechanism. For this reason, combat shotguns saw only limited use on the Western Front and had no major impact on the course of the war.

Another proposed solution to the individual firepower problem was to arm infantrymen with a faster-firing self-loading rifle. Only one belligerent nation, France, managed to successfully deploy such a weapon, fielding around 86,000 RSC M1917 rifles during the last year of the war. However, the rifle was expensive to produce and unpopular with French troops, being somewhat unreliable and difficult to maintain under trench warfare conditions. It would not be until the introduction of the American M1 Garand in 1936 that an army would be equipped with a self-loading rifle as its standard infantry weapon – and for more on the evolution of infantry rifles, please check out our previous video What Actually Defines an Assault Rifle, and Who Invented Them?

In the end, most nations elected to produce lighter machine guns that could be carried into combat by a single infantryman – attempts which met with varying degrees of success. For example, the German light machine gun, the MG.08/15, was produced by removing a standard MG.08 Maxim gun from its heavy tripod, lightening a few components, and fitting it with a shoulder stock, pistol grip, and bipod. Despite these modifications, the 08/15 still weighed a whopping 18 kilograms, making it difficult to use and extremely unpopular with German troops. Indeed, in modern German, the idiom “Oh-eight-fifteen” is still used to describe something unremarkable or uninspired. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the French Chauchat light machine gun, also introduced in 1915, weighed only 9 kilograms. Though it was the most widely-produced and deployed automatic weapon of the war, the Chauchat’s effectiveness was somewhat hampered by design flaws like its open-sided magazine that tended to accumulate dirt and mud. Perhaps the most effective of the Great War light machine guns was the British Lewis Gun, which weighed 13 kilograms and could deliver effective sustained fire from a 97-round pan magazine. A close runner-up was the American 7-kilogram Browning Automatic Rifle or BAR, which unlike its contemporaries was designed to be fired from the shoulder or the hip. A contemporary doctrine known as “walking fire” called for light machine guns like the BAR to be fired from the hip while marching, keeping the enemy’s head’s down as a unit advanced. A special belt with a cup to support the BAR’s shoulder stock was even issued for this purpose, though none are known to have been used in combat.

But whatever their relative advantages, all these weapons suffered from the same flaw: they fired full-power rifle cartridges, which were heavy to carry, overpowered for the short distances over which combat typically took place, and made light machine guns difficult to control in fully-automatic fire. In the end, it was the Germans who came up with the most practical solution by creating an automatic weapon chambered in a lighter pistol-calibre cartridge – the world’s first submachine gun. While the first pistol-calibre automatic weapon to see combat was the Italian Model 1915 Villar-Perosa, this was largely used as an aircraft machine gun and squad support weapon and did not fit the modern definition of a submachine gun. At first, the Germans attempted to modify existing pistols such as the Mauser C-96, and Luger P.08 to fire fully-automatically, but these weapons were unsuccessful, as their high rates of fire – 1200 rounds per minute for the Luger – made them uncontrollable and drained their magazines in seconds. It was thus decided to design a suitable weapon from scratch. The result was the Bergmann MP 18, designed by pioneering weapons engineers Theodor Bergmann and Hugo Schmeisser. 83 centimetres long and weighing only 4 kilograms, the MP 18 was chambered in the 9mm Parabellum cartridge, had a rate of fire of 400 rounds per minute, and was fed from a 32-round drum magazine mounted on the left side of the weapon. Introduced in early 1918, the MP 18 was used to great effect by German Sturmtruppen or “stormtroopers”, specialized groups of elite troops who used speed, maneuver, and advanced light weapons to break through enemy lines and create breaches through which regular troops could advance. But the weapon was not perfect, the heavy side-mounted drum magazine making it unbalanced and awkward to handle. Later versions would use lighter stick magazines.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, another pioneering weapons designer was thinking along similar lines. Born in 1860, Brigadier General John Tolliver Thompson was a career U.S. Army officer who from 1890 to 1914 served as Director of Arsenals for the Army’s Ordnance Department. During his tenure, he was responsible for the testing and adoption of the 1903 Springfield rifle and the selection of .45 ACP as the Army’s standard pistol cartridge. Disturbed by the deadlocked trench warfare taking place overseas and sensing the United States’ impending entry into the Great War, Thompson came up with what he called a “trench broom”: a portable automatic weapon that would allow troops to quickly clear out enemy defensive positions. With the backing of tobacco magnate and financier Thomas Ryan, in 1916 Thompson formed the Auto Ordnance Company and set about developing two different weapons: an automatic rifle chambered in the Army’s standard .306 [“Thirty-ought-six”] cartridge and a smaller handheld machine gun chambered in .45 ACP. A major design challenge facing Thompson was what kind of delay mechanism to use in his new weapons. All self-loading firearms – that is, those which use the energy from one round to load and fire the next – require some kind of mechanism to delay the opening of the action, otherwise hot propellant gas will leak back into the shooter’s face, the bullet will exit at a lower velocity, and the bolt will shoot backwards so violently it may damage the firearm. One common solution is to use the recoil of the firearm’s barrel or propellant gas tapped off from the barrel to unlock the bolt, but Thompson rejected both designs as too heavy, bulky, and unreliable. Instead, he selected a mechanism based on an unusual physical phenomenon discovered by U.S. Navy Commander John Blish. While serving aboard the warships USS Niagara and USS Vicksburg, Blish noticed that naval guns with interrupted-screw breeches stayed closed when fired with a heavier charge but tended to unscrew when fired with lighter charges. This led Blish to conclude that dissimilar metals had a higher tendency to stick together when subjected to high pressure – a phenomenon he dubbed the Blish Effect. The Thompson gun’s action exploited this effect using a brass block sliding in an angled channel on the weapon’s steel bolt. When the weapon was fired, the rearward pressure exerted by the cartridge caused the brass and steel to stick together, delaying the opening of the bolt. Once the chamber pressure had dropped to safe levels, the brass block slid out of the way and released the bolt, allowing the action to cycle. The initial version of the weapon, dubbed the “Persuader” or “Annihilator”, did not have a shoulder stock and was designed to be belt-fed like a heavy machine gun. However, this development went nowhere and the weapon was modified to take conventional box magazines. It was also given the less sensational name “Thompson Submachine Gun.” Interestingly, this now-universal term was coined by Thompson himself; previously such weapons were known by variations of the term “machine pistol.”

Though a few prototype guns had been completed by late 1918, unfortunately for Thompson – but fortunately for the rest of the world – the Great War suddenly came to an end, dashing Auto Ordnance’s hopes of obtaining large government contracts. Undeterred, Thompson decided to try his luck on the civilian market, and in March 1920 contracted the Colt Manufacturing Company of Hartford, Connecticut to produce an initial batch of 15,000 weapons, which was completed in 15 months. As it turned out, these would be both the first and the last Thompsons to be manufactured for nearly two decades.

First released onto the market in 1921, the first model Thompson Submachine Gun was 86 centimetres long, weighed 5 kilograms, and featured a distinctive ribbed barrel and forward vertical grip. Chambered in .45 ACP, it had a rate of fire of 800 rounds per minute and could feed either from 30-round box magazines or from 50 and 100-round drum magazines. Later versions of the Thompson were fitted with a device called a Cutts Compensator, which deflected propellant gases upward to prevent the muzzle from rising and make the weapon more controllable in automatic fire.

Yet to Thompson’s disappointment, his supposedly world-beating weapon failed to find any customers. For year after year, most of the 15,000 Thompson submachine guns lay gathering dust on warehouse shelves, slowly eating away at the Auto Ordnance Company’s remaining capital. Part of the problem was timing. With the Great War over, armies around the world were demobilizing, with few purchasing any weapons in quantity – let alone fancy new ones like the Thompson. But the Thompson’s main flaw was its cost. The Thompson was a complex design to manufacture, requiring dozens of machining operations which, in the era before computer-controlled manufacturing, each had to be made using a separate piece of complex machinery. This resulted in a manufacturing cost of $44 per gun – equivalent to nearly $600 today. Auto Ordnance in turn sold the guns to its distributors for around $150 apiece, while the final retail price was an eye-watering $200. For comparison, the average worker at the time made around 90 cents per hour, while a brand-new automobile could be purchased for between $400-500. This made the Thompson a difficult investment to justify, particularly with so many other, cheaper firearms on the market. Nonetheless, Auto Ordnance embarked on an extensive European marketing tour, searching high and low for anyone to purchase their fancy new guns. Special military versions of the Thompson were proposed, including models chambered in more powerful cartridges and fitted with bipods for use as light machine guns. The German Junkers aircraft company even came up with a version of their F.13 transport plane armed with no fewer than 30 downward-firing Thompsons for use as a ground-attack platform – because even in the 1920s, there was no kill like overkill. But most of these efforts came to nothing, with European militaries showing little interest in the gun. One client Auto Ordnance tried particularly hard to court was the Royal Ulster Constabulary, which at the time was engaged in a bitter struggle against insurgents fighting for Irish independence. But while the RUC was not interested, their rivals, the Irish Republican Army, most definitely were, and purchased and smuggled several hundred Thompson guns into Ireland for use in the Irish Civil War of 1922-1923. Back home, the US Air Service and Cavalry tested the gun but rejected it, while private sales continued at a slow trickle – the main purchasers being banks, police departments, and large corporations, the latter of which found Thompsons particularly useful as, shall we say, labour negotiation tools.

Meanwhile, Auto Ordnance’s attempts to develop and sell its second product, the Thompson Auto Rifle, were also going poorly. Though the company managed to get the weapon into trials for the US Army’s new service rifle, its performance was less than stellar. The bolt recoiled so quickly and ejected spent cartridge cases so violently that in testing the cases embedded themselves in a wooden block held beside the rifle. The rifle also required lubricated cartridges to operate reliably, ultimately leading to its rejection by the Ordnance Department. Alarmingly, these trials revealed that the heart of the Thompson system, the Blish Lock, did not actually work as designed. Indeed, the Blish Effect itself was found to not even exist, meaning that the Thompson’s sliding brass block did almost nothing to delay the recoil of the bolt. That the submachine gun worked at all was due to the bolt being heavy enough for its sheer inertia to delay its recoil, in reality making the Thompson mechanism a simple straight-blowback action. With the Thompson Auto Rifle out of contention for US Army’s adoption, Auto Ordnance abandoned the project and turned its attention to its more effective – but still commercially unsuccessful – submachine gun.

The company’s first big break came in 1926, when, following a series of robberies, the US Postal Inspection Service purchased a batch of 200 Thompsons to arm United States Marine Corps troops assigned to guard mail trains. The Marines fell in love with the Thompson, and in 1928 ordered another large batch, specially modified to have a slower rate of fire to improve controllability and ammunition consumption. The guns, designated the model 1928, saw extensive use in Nicaragua, Panama, Honduras, and other countries during the so-called “Banana Wars” – a series of military interventions in Central America and the Caribbean intended to secure American political and business interests in the region. The Marines later carried Thompsons into China as part of the U.S’s policy of “gunboat diplomacy.” Chinese warlords were impressed by the weapon, and many locally-manufactured copies were produced. Small numbers of Thompsons were also purchased by the Coast Guard for use against rum runners, while in 1928, the US Cavalry, which had previously rejected the Thompson, bought a batch for use by armoured car crews. But while this uptick in sales was a welcome development, by 1928 Auto Ordnance had only succeeded in selling 6,000 of its initial batch of 15,000 guns.

At this point, you might be asking yourself: “but what about the gangsters?” Alas, while popular culture would have us believe that every Prohibition-era bootlegger had a trusty “Chicago Typewriter” hidden in his violin case, the reality was considerably less dramatic. As mentioned before, for most people the Thompson was a prohibitively expensive weapon, so much so that only 10% – that is, around 150 guns total – of the initial 1921 batch were ever sold to private individuals. This meant that while several gangs did indeed purchase and use Thompsons, they were nowhere near as prevalent as is commonly believed. But Hollywood has never been one to let the truth get in the way of a good story, and the popular gangster films of the era such as Scarface, G Men, and Angels with Dirty Faces placed the iconic “Tommy Gun” front and centre, cementing its mystique as the “gun that made the twenties roar.” Such media depictions skewed popular perceptions of the prevalence of violent crime, spurring many police departments to purchase their own Thompsons in order to counter this perceived threat. Sales further increased following the 1929 St. Valentine’s Day Massacre and the 1933 Kansas City Massacre, in which a group of gangsters including Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd gunned down four policemen. The latter incident prompted the FBI to purchase its own batch of 115 Thompsons in 1935. Other gangsters and bandits of the era known to have favoured the Thompson included “Public Enemy No.1” John Dillinger, George “Machine Gun” Kelly, and George “Bay Face” Nelson, who himself met his end in a hail of FBI Thompson bullets on November 28, 1934.

The year 1928 was a pivotal one for the Auto Ordnance Company, for it was in that year that Brigadier General John Thompson retired and stepped down as head of the company. That same year, the company’s main financier and majority stockholder, Thomas Ryan, died at the age of 77. His estate, seeing Auto Ordnance as a money-losing boondoggle, immediately attempted to liquidate the company. The remaining shareholders succeeded in delaying the sale by more than a decade and in selling most of the company’s remaining inventory, but in 1939 Auto Ordnance was finally sold to one Russell Maguire, a notorious corporate raider.

Those viewers familiar with 20th Century history might recognize 1939 as the year the Second World War broke out, meaning that much to the chagrin of Thomas Ryan’s estate, the previously unsuccessful Auto Ordnance Company was about to experience a major reversal of fortune. With the worldwide demand for firearms suddenly soaring, in December 1939 Maguire signed a contract with the Savage Arms Company of Westfield Massachusetts to produce Thompson guns for foreign export. As part of their previous contract with Colt, Auto Ordnance owned all the manufacturing tools for the Thompson gun, meaning that by May 1940 the first new batch of guns in nearly two decades was already rolling off the production line. The first major purchasers of the new Thompson were France and Great Britain, who were scrambling to rearm in the face of an imminent Nazi invasion. The latter purchase was particularly ironic as for decades the British had dismissed submachine guns as “gangster guns” with no place in honourable warfare. But with insufficient arms manufacturing capacity at home, Great Britain had no choice but to import hundreds of thousands of American Thompson guns to arm the British Expeditionary Force and Home Guard. Despite its weight, the gun was well-liked by British troops, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill was famously photographed shooting one during an inspection of coastal defences. Propagandists on both sides had a field day with this photo op, with Allied propaganda emphasizing Churchill’s status as a “fighting leader” while Nazi propaganda painted him as a dangerous “gangster.” In the end, however, a combination of limited cash reserves and the loss of thousands of weapons on the beaches of Dunkirk meant that the British were never able to acquire enough Thompsons, and were forced to turn to a much cheaper – and cruder – alternative to make up the shortfall: the much-maligned “plumber’s nightmare” – the Sten Gun – and for more on this, please check out our previous video The Pivotal WWII Gun Nobody Wanted to Put Down.

Meanwhile, in December 1941 the United States entered the war, further driving up demand for Thompsons. However, the original 1921 and 1928 models were far too expensive for mass adoption, forcing Auto Ordnance to make a series of cost-saving modifications. The rear sight was greatly simplified, the ribbed barrel smoothed down, the iconic vertical grip replaced with a simpler horizontal version, and the Cutts Compensator eliminated, creating the model 1928A1. With a final purchase price of only $70, around one million 1928A1s were produced between January and June 1942, when production switched to the even simpler and cheaper M1 variant. The M1 did away with previous versions’ complex – and useless – Blish Lock, allowing the receiver and bolt to be greatly simplified and the bolt handle to be moved from the top to the side of the weapon. Barely four months into the first production run, the M1 itself was replaced by the even simpler M1A1, whose design cut 10 hours off the production of each gun and dropped the government purchase price down to $43 per unit. The M1A1 would go on to become the iconic American submachine gun of WWII, with nearly 1.3 million being manufactured by Savage as well as Auto Ordnance in its own factory in Bridgeport Connecticut.

But even in its cheapest, most simplified form, the Thompson was still too complex and expensive to keep up with the insatiable demands of the US war machine. So, in 1942, the U.S. Army Ordnance Board took a page from the British and began developing a new submachine gun that could be produced far more cheaply and in greater numbers than the Thompson. The resulting weapon, designed by engineers George Hyde and Frederick Sampson of General Motors’ Inland division, was, like the British Sten Gun, built mainly of welded steel stampings, bringing its manufacturing cost down to only $20.94 – less than half of the M1A1 Thompson. Furthermore, its manufacture did not require specialized machine tools, allowing the gun to be produced in a wide variety of factories. Indeed, most of the guns produced during the war were manufactured by GM’s Guide Lamp division, which had previously made car headlamps. Formally adopted in December 1942, the new weapon was officially designated the M3 Submachine Gun, though due to its resemblance to a certain mechanic’s tool it was universally known to the troops as the “Grease Gun.” Though the Grease Gun was intended to replace the Thompson, problems with tooling up the M3 production line meant that production of the M1A1 Thompson continued until February 1944, with the gun continuing to serve until the end of the war. While the M3 was cruder and slightly less accurate than the Thompson, it was nonetheless an effective weapon and well-liked by U.S. soldiers. 655,000 were produced before the war ended, and while the M3 was officially dropped as a standard service weapon in 1957, a handful remained in service as personal defence weapons for tank crews until as late as 1992.

As for the Thompson, the end of WWII brought its 20 years of military service to a close. While certainly an iconic weapon, the Thompson was a design from an earlier era whose complex and expensive manufacturing process made it ill-suited to the modern era of industrialized warfare. Yet its legend lives on in movies, TV shows, and other pieces of popular media, where the “Chicago Typewriter”, in the hands of fictional gangsters and lawmen, continues to make the 1920s roar.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Lawrence Massacre of 1863

- The Largely Forgotten Los Angeles’ Chinese Massacre

- This Day In History: September 24th- The Murder of Neil LaFave

- The “House of Horrors” Hotel and One of America’s First Serial Killers

Expand for References

McCollum, Ian, Thompson 1921: The Original Chicago Typewriter, Forgotten Weapons, October 6, 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=QN1uUfMCQ0Y&t=982s

McCollum, Ian, The Marines’ First SMG: 1921/28 Thompson Gun, Forgotten Weapons, October 9, 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=O4jo8csYpg0

McCollum, Ian, World War Two Heats Up: the M1928A1 Thompson SMG, Forgotten Weapons, October 11, 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=KTY_DQ0mllU

McCollum, Ian, The Iconic WW2 Thompson: the M1A1, Forgotten Weapons, October 15, 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=1_8qLFoMzl4

Smith, Charles, John Thompson and the Thompson Submachine Gun, Auto Ordnance, https://www.auto-ordnance.com/history-of-an-icon/

The Thompson Submachine Gun Story, NFA Toys, http://www.nfatoys.com/tsmg/

Moss, Matthew, The Tale of the Tommy Gun, Popular Mechanics, February 27, 2017, https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/weapons/a25414/tommy-gun-thompson-submachine/

The post The Story of the Iconic ‘Tommy Gun’ appeared first on Today I Found Out.